-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 8 months ago

Critical Stages’ Come to Where I Am is illuminating the potential of performance online, says Robert Reid

With its remit to take theatre to “enable regional communities to have the same access to high qua […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 8 months ago

The proposed closure of Monash University’s CTP is a devastating blow to Australian theatre culture, says Robert Reid

As I sat waiting for my next zoom class to start, the news emerged via Twitter – from Pro […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 9 months ago

The present crisis in Australian theatre offers a unique opportunity. Robert Reid explains why we musn’t blow it

This is a crucial moment for Australian theatre, a moment when it is vital that we don’t r […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 9 months ago

If some real thought were applied to the MTC’s audio treatment of The Turn of the Screw, says Robert Reid, it could have been amazing

Ugh… and I thought that the Audio Lab’s Great Australian Speeches lacke […]

-

Beautiful voices, beautiful, rhythmic and readable prose. But I wondered what the director actually did, apart from hand out six copies of the book and a packet of highlighter pens. Robert is so right – MTC are leaving most of the medium unexplored.

They can do so much better, and I’m sure they will. This project deserves, and needs success because I believe it should stay, part of live theatre’s presence in cultural consciousness, more than just a pandemic stopgap.

-

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 9 months ago

Caitlin Beresford Ord embodies a forgotten Australian vaudeville star in Black Swan’s The Perfect Boy. Robert Reid checks it out

On stage is an upright piano, dimly lit sheet music laid out on its face. A h […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 10 months ago

Audio drama has a long and luminous history. So why does the MTC’s Audio Lab turn away from…theatre? Robert Reid reports

For Australian theatre, the turn to online performance has been a long time coming. I […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 10 months ago

Robert Reid relishes the chance to finally watch Ilbijerri’s classic, Jack Charles V The Crown

One of the very, very few good things to have come out of lockdown is that a work like Jack Charles V The Crown is […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 10 months ago

It’s not the same as being there but, says Robert Reid, Redline Productions’ live streamed Thom Pain (Based on Nothing) offers something else

There is something mesmerising about the combination of Will Eno […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 4 years, 11 months ago

Maybe traditional performing arts could learn a lot from YouTube vloggers and online games. For the launch of BLEED 2020, Robert Reid investigates live digital performance

Now, stop me if you’ve heard t […]

-

Hey Matt, yeah you’re absolutely right about it being a fine line between involving amateurs and exploiting unpaid performers. I think the best way to manage that is to see it as a fluid thing, that as volunteers become increasingly involved that they should be able to move into paid work. The ARG and LARP communities have had a habit of playing fast and loose with this which i think comes from their own often amateur backgrounds (along with even more concerning occupational health and safety issues). With my old company, Pop Up Playground, we regularly had people join us from the community as participants who became so essential to the process that we took them on as paid members of the company. Thanks for writing back, really interesting

-

-

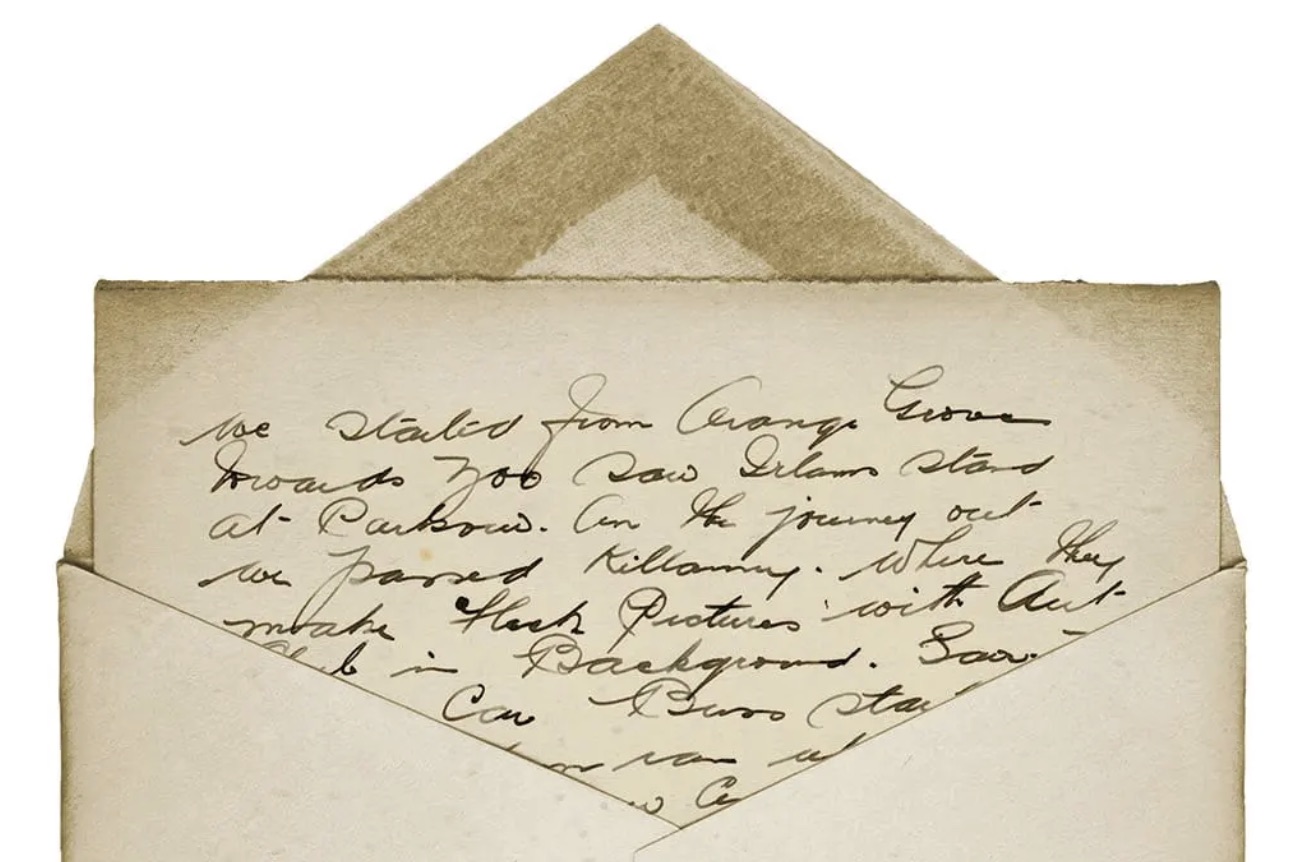

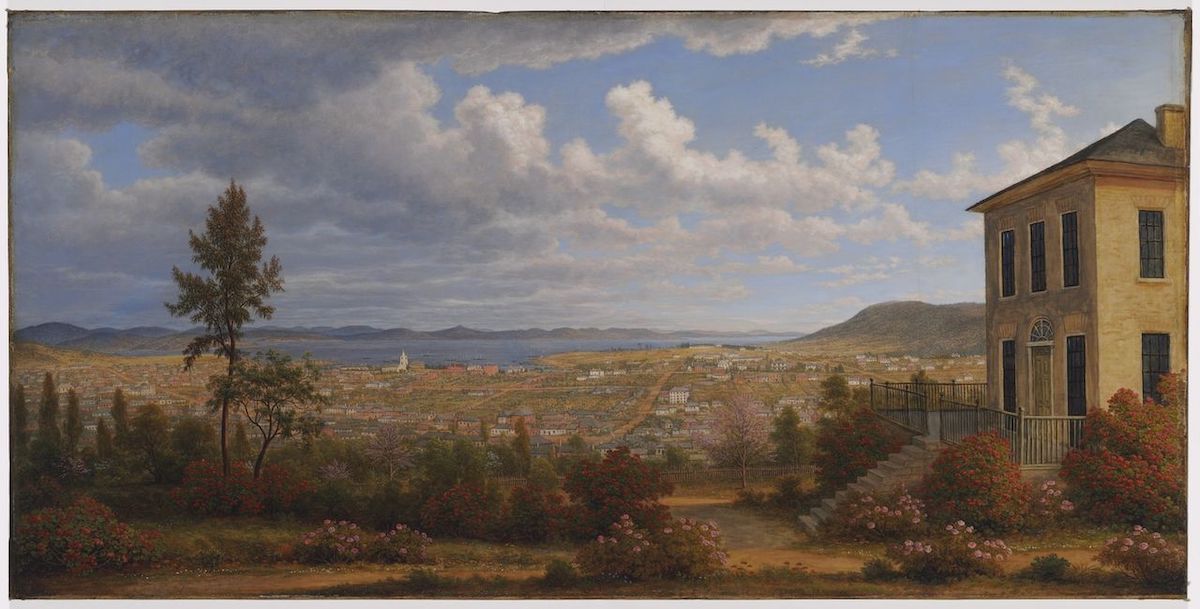

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years ago

Robert Reid continues his exploration of the hidden corners of Australian playwriting with a story of colonial Tasmania, Catherine Shepherd’s 1938 play Daybreak

Catherine Shepherd (1901-1976) was born in […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years ago

Now we’re all extras in a disaster movie, Robert Reid thinks through the dramaturgy of pandemic

It is too much. The writing, the thinking, the caring… it is too much. I cannot make, move, think under the wei […]

-

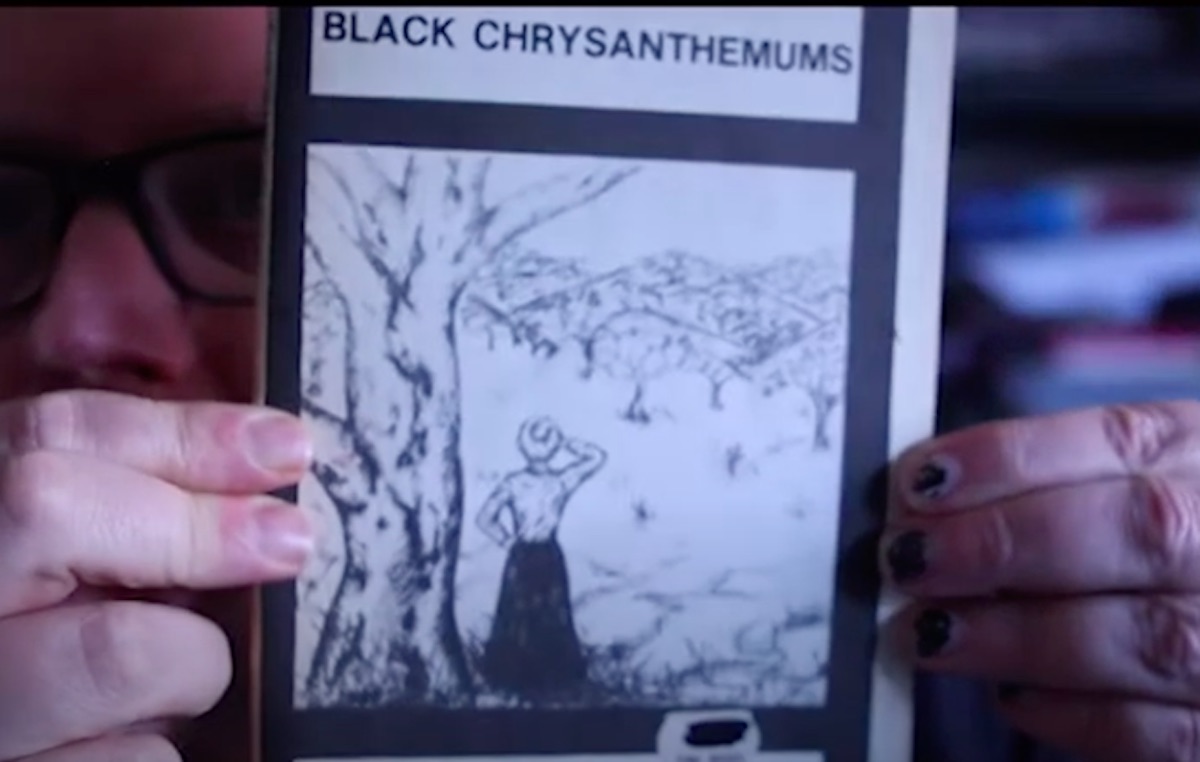

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years, 1 month ago

Robert Reid continues his isolation reviews of Australian plays with Angela Fewster’s Black Crysanthemums

According to John McCallum, Adelaide playwright Angela Fewster play Black Chrysanthemums “roused some […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years, 1 month ago

In the first of a new video series focusing on lesser known works in the Australian canon, Robert Reid reviews Dorothy Blewett’s 1941 play Quiet Night

Plays have always been strange literary animals, half way […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years, 2 months ago

A surprisingly gentle and empathic play that leaves a

haunting sadness: Robert Reid on Daniel Keene’s The CurtainDaniel Keene’s The Curtain at fortyfive downstairs is a play of surprising

gentleness, deep sad […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years, 2 months ago

Robert Reid encounters an exuberant masculinity in Between Tiny Cities

We stand in a circle. A wide, broken white outline drawn on

the floor delineates the performance space from the audience. The inside of […]

-

Robert Reid commented on the post, Adelaide Festival: The Doctor 5 years, 2 months ago

Oh, James, excellent critique,thank you!

You’re much more generous with the audience than i’m prepared to be. I think you’re analysis of the text and the dramaturgy of it is spot on. I can’t say i’m swayed to think any better of the audience’s laughter though. Sure, its posible that each of them was enjoying the cleverness of the drafting…[Read more] -

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years, 2 months ago

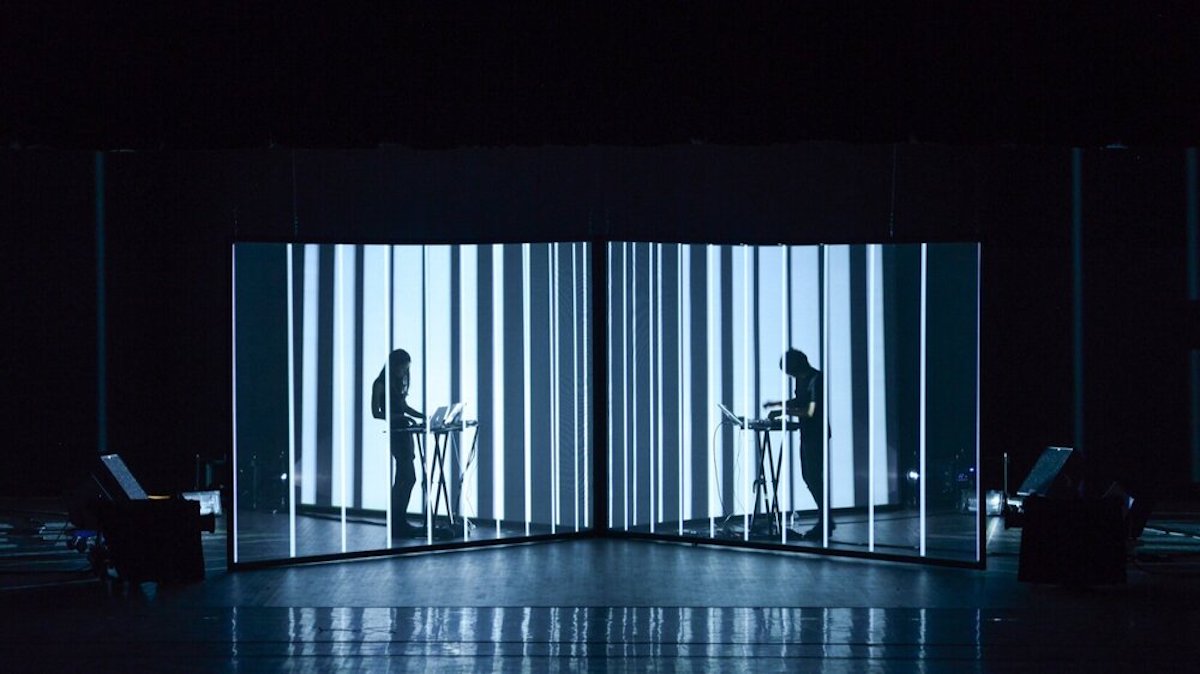

NONOTAK’S Shiro is a hypnotic encounter with pure aesthetic, says Robert Reid

It’s not often – at least for me – that one has a purely

aesthetic encounter. NONOTAK’s Shiro is

just such an experience. No possib […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years, 2 months ago

The virtual reality experience Eight leaves Robert Reid spellbound

This is a remarkable experience. I’ve often found VR to be a

somewhat underwhelming phenomenon, demanding you stay in place and only l […]

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years, 2 months ago

‘I keep wanting to close my eyes and just listen to the music’: Mozart’s Requiem is magnificent, but Romeo Castelluci’s visuals leave Robert Reid cold

I should preface this by saying I’m no real fan of Caste […]

-

Castellucci Lite.

Diet Castellucci.

Castellucci Zero.Castellucci reaching into his satin bag of tricks. The baby, the smashed car, the body disappearing into the bed, the faces stretching behind black satin. All of them pulled from previous works. The baby from ‘Tragedia Endogonidia,’ the car from ‘Paris,’ the melting/disappearing woman from ‘Hey Girl,’ the black stain faces from ‘Inferno.’

But there was a ‘genuine’ moment for me: when the chorus were writhing across the dirt like maggots and three naked men walked blindly through the darkness, one leading the other. Did I understand it? No. Was I aware of myself “making-meaning” as the work unfolded? Sometimes. Did the work feel like a peculiar form of cultural elitism? Yes. Do I have creditors calling me daily because the tickets were so impossibly expensive? Absolutely!

I spent the ninety minutes thinking about two things. First, a comment I overheard while the orchestra was tuning: ‘oh I do love that sound!’ I agreed. It’s a nice sound. But is it fetishising the form? Are we just sitting here for the cultural capital? The chance to say we went to the opera/theatre/dance, whatever? Maybe a nice bit of music that we’re ‘all’ familiar with? The audience were practically humming the Lacrimosa, which I attribute solely to that scene in The Big Lebowski. But are we saving this up for the next dinner party, where we can finally say “well WE saw this interesting Italian Director do a Mozart…(and maybe you didn’t because, ha-ha, it sold out!)” And then I thought, cynical but, maybe that’s precisely its function. ‘The Big Festival Function.’ A ritual where we literally ‘spend real time’ in exchange for ‘symbolic time’? A cultural-credit system. And if the work happens to be any bloody good, well, lucky us. But that’s not really what we’re here for. We’re here for the Opera, dammit! We’re here for the selfie! And on opening nights, we’re here for the booze!

The rest of the time I was watching the top of the walls/theatre flats shake when the performers danced. That’s my takeaway. I had thought Castellucci was well-loved because of the ‘immobility’ of the images he creates. As you said, precise, perfect. Mechanically engineered within an inch of its life. He’s trying to show the spirit in the machine, or the Geist of history, or something like that. But these images didn’t feel like the genuine-article. It felt a cheap-counterfeit. Mass-produced. Obsolete before they even roll off the factory floor. And if the machine don’t run, it’s hard to see the spirit that moves it.

-

-

Robert Reid wrote a new post 5 years, 2 months ago

‘This is some of the best writing I’ve seen in a long time’: Robert Icke’s production of The Doctor at the Adelaide Festival leaves Robert Reid transfixed and enthralled

Warning: spoilers abound

In the g […]

-

Any group is heterogeneous. Although the “grey-haired middle class” might share some common economic and political views, I’m not sure we can assume very much about the thoughts that go through their heads during a performance. Laughter isn’t always a very good indicator, either. I’m often surprised by audiences. We like to speak about them and for them. But rarely to them. They often turn out to be more progressive than we first realised, more open-minded than we imagine. And isn’t this, in a way, exactly what The Doctor examined? Our assumptions? Our ‘groupings’? One lexicon against another. . .

I would hate for someone to guess the source of my laughter. Especially if they then drew conclusions about my politics. Just as I would hate it if someone did the same for the clothes I wore or the way I speak. . . Our histories might be collective. But our thoughts are individual. These semiotic assumptions are dangerous.

The laughter at the beginning of the second act (the ‘literally’ and ‘figuratively’ sequence), might not have come from the audiences shared conviction that language is decaying. I laughed. But I was laughing at something else.

Here’s Dr. Wolff’s monologue in full:

WOLFF: “Literally means literally, not figuratively – in fact the whole point of the word literally is so that we can indicate that we’re not speaking figuratively. it’s a word to say that a thing actually happened. Use literally figuratively and you’ve successfully destroyed the whole purpose of the word. So when is ay that the people I work with are literally fat fucking ignorant pigs wandering around on their hind trotters, you now don’t know whether I actually work with medical pigs or whether I’m just speaking figuratively”

When I laughed at that, I wasn’t laughing because I agreed. I was laughing because the image of doctors-as-pigs walking on their trotters is fairly amusing. I was laughing because the indignation about something so pedantic was unexpected. The conservative/reactionary sentiment of Wolff (“when the end comes, it shows itself first in language”) only occurred to me as a secondly phenomenon. The effect of the dramaturgy is that of a one-two punch. First, we laugh at the image. Second, we realise the full implication of the monologue. It’s not a ‘hear, hear’ moment. It’s an ‘oh dear’ moment: ‘oh dear, I hope the person next to me doesn’t think I believe that language is decaying. I hope they know that I was laughing at the pig line, not that other bit. . .’

This ‘bait and switch’ happens again and again. It’s no coincidence that the priest is one of the last characters to be revealed as a person of colour (over an hour into the performance). The dramaturgy plays off our over-determination of whiteness, as such. It ‘wants’ us to assume the priest is a white male . . . I don’t think this is as much a personal thing. I don’t think it’s about white-saturation, or positionality. I think it is, first and foremost, an objective condition built into the dramaturgy. Our personal experience and our assumptions only emerge afterwards.

During the live Q&A scene the dialectic emerges clearly. I think more than a confrontation of personalities, it’s actually a confrontation of theories. Modernism against postmodernism. Science against Political/Cultural Theory. STEM against Humanities. It’s precisely because these two sides fail to speak to one another, because they are siloed, that meaningful communication seems impossible. In that moment, each of these experts attempt to force their own ideological framework onto the situation. But in doing so, they ‘warp’ it. None of their frameworks quite fit.

There are five panellists. The first, “a minister and activist on behalf of Creation-Voice, which is a nondenominational Christian group who works on political policy,” suggests that Wolff is prejudice against Christians because of her Jewish heritage. The second panellist, a medical ethicist working on the “campaign against abortion,” accuses Wolff of performing the abortion herself. The third panellist, “a senior reader in Jewish history” accuses Wolff of sexism (“you believe it’s OK to discriminate to have [hire] more women?”). The fourth, a post-colonial academic and activist, homes in on the historicity of word “uppity” and claims Wolff was racially motivated. The fifth panellist, “a researcher and the chair of a nationally recognised campaign group for the understanding of unconscious bias and the furtherance of racial sensitivity,” begins by insinuating Wolff’s ‘problems’ arise from her being private-schooled.

The bait and switch, again. We laugh because of the stiffness of the panellists. We laugh at their self-imposed titles. Their utter conviction that they are correct. Not without pride, not without arrogance and a ‘know-it-all’ posture. We laugh at the impossibility of these frameworks. The event central to the work shifts as we apply different ideological lenses to it. They replay the scene in a different light. But none of them provide a holistic understanding of the event. The event is too slippery. The theoretical frame cuts into the clay of reality, and distorts it.

None of the panellists saw the instigating incident. We, the audience, did. They rip into Wolff with such self-assuredness. They’re so damn certain they have the answer. They tell Wolff what happened, they re-write history to suit their aims. But we, the audience. . . we were actually there. We know what Wolff’s gone through. We know her cat was murdered. her car vandalised. Her career over. We suspect she has suffered great loss. We know the mob is after her. And now these panellists . . .

What, I think, we respond to, firstly, is the Event of the Q&A itself. It IS an inquisition. Complete with a panel (of judgement) behind a table and a live-feed up close of Wolff’s face. The media machine whirrs in the background. If a tear does fall, we’ll bloody well catch it. Her misery is our entertainment. Only later, after we respond to the event, does the ideological content emerge. What the panellists say . . . it’s not without merit. But when it’s directed against Wolff, it’s horrifying. It’s personal. She’s exposed. It’s terrifying to watch.

The character of Dr. Copley says it best, when he says: “there is really nobody, no human being on this earth that does not defy that sort of simplistic bullshit with their technicolour, thousand-fold complexity.” This sentiment is reiterated by the priest right towards the end of the work: “every person is a city full of people. We all contain a thousand different selves, and . . . we choose which selves we want to put in charge.” No sides are really correct in this debate. They’re all wrong and right to varying degrees. That’s what made it good drama.

Conspicuously absent from the work is any real notion of class. Sure, there’s a mob somewhere,

vague and offstage. But isn’t a mob just a group “in which the residue of all classes are

represented” (Arendt)? There’s some vague reference, maybe, to the siphoning of public

money into private interests (Wolff’s hospital is a private one). But I want to pull the rug out

from the whole thing. Because no matter how wonderfully complex and vital The Doctor was, it

doesn’t address the backdrop of global exploitation (of humans and nature) and failed

economic models that wreak havoc. Even Alzheimer’s, as devastating as it is, feels a first world

problem against dysentery, starvation and the twelve-hour working day. I know I’m shifting the

goal-posts. But it was a bourgeoise work for a bourgeoise crowd. Can we really critique the white-haired middle class for enjoying what was, in the end, made for them? -

Oh, James, excellent critique,thank you!

You’re much more generous with the audience than i’m prepared to be. I think you’re analysis of the text and the dramaturgy of it is spot on. I can’t say i’m swayed to think any better of the audience’s laughter though. Sure, its posible that each of them was enjoying the cleverness of the drafting and the absurdity of the imagery, and its almost certainly my own prejudices that make me read their responses rather more harshly than that, but i still can’t shake what you call my semiotic reading of them as an audience, as a collective, dangerous though that is. I can’t help but see a pattern of response emerging over the whole, the laughter and applause for the language monologue, the laughter at the perhaps pompous and covoluted job titles, all signal something bigger than individual appreciation of the ironies in these moments. You note that thre’s no mob, that its somewhere out there only obliquely refered to. I’d argue that the audience is that mob, not gunning for Wolff necesserily, but certainly sitting in judgement, and i think that mob mentality finds its way out in those moments of bourgeoise confirmation and rejection. Laughter can function as a sign (dangerous semiotics again) of group identity, it can tell those around us that we think similarly, that we have all recognised a thing. Granted it doesn’t tell us the individual details of what we think the others have recognised, but all mobs are made up of individuals. Some of them are maybe worried about the destruction frankensteins monster may cause, some of them maybe wondering what the monster has to say about the human condition and some maybe amused by the irony that the real monster here is the mob – none of that stops them picking up the pitch forks and torches and marching on the castle….

But that’s just my reading and, as i say, it is filtered through my own cycnicisms and prejudices. One of the things i thought The Doctor did so well was the way it used that bait and switch to reveal my own assumptions to me all the way through. Maybe the bourgeoise audience were having the same experience in those moments and thinking, oh should i have laughed at that, but if its a a bourgeoise work for a bourgeoise crowd, and they enjoy it in all the ways its been made for them to enjoy, then i think we can judge them for enjoying it, and of course thats exactly what i did.

We also didn’t actually see what happened in the room either. The production pauses in the crucial moment when the violence occours. we never see if Wolff strikes the preist, only her advance upon him and then his retreat saying get your hands off me. The production shuts us out of that moment so we’re as much in the dark as the panelists as to what exactly happens then, and so like the mob, we make our decisions as to what we beleive happened (from the signs constructed around the absence) and then respond collectively.

As i say though, terrific analysis and excellent to have here as a counterpoint to my rambling thoughts. -

Great riposte!

Thanks for taking the time to reply.

I’ll only maintain that we have to be careful.

We can’t immerse ourselves in a pessimism that has no future.

-

- Load More

University theatre departments teach students about collaboration. And that’s really important. They provide opportunities for theatre workers—productions, residencies, short- and long-term employment. And that’s also really important. They’re a vital part of our cultural and educational ecology. And my heart breaks every time I hear that we’re losing yet another university theatre department.

Absolutely terrific article, Robert; so succinctly and eloquently argued.