Performance photographer Pia Johnson reflects on the many roles that photography can play in the theatre: as memory, as dramaturgical device and as an art in itself

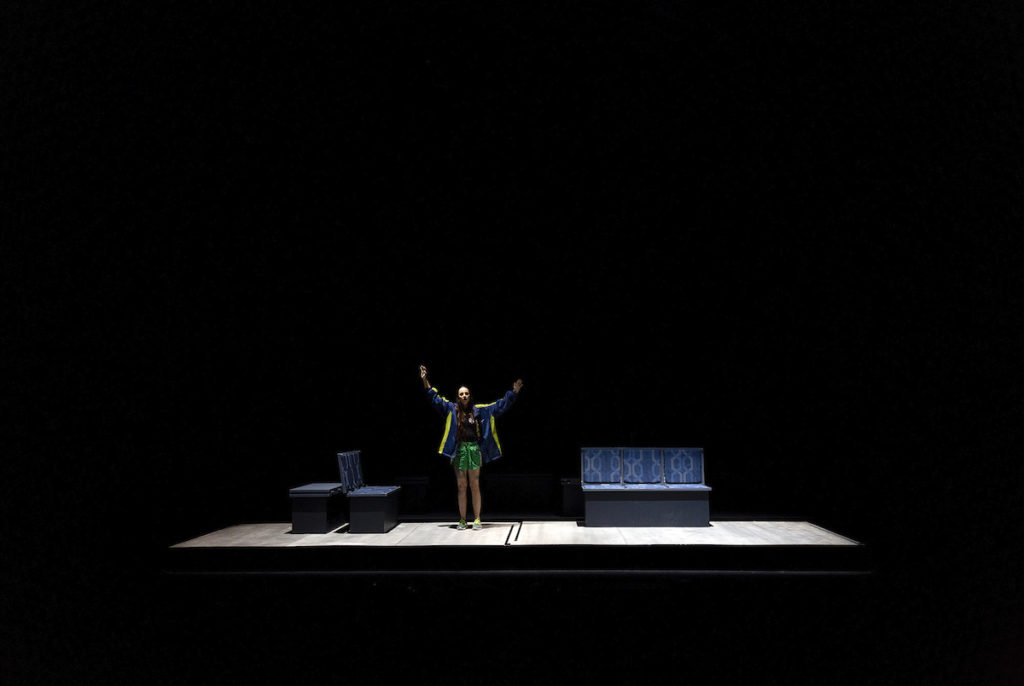

Being forced to stay home in these strange, uncertain times has given me the chance to look through my archive of performance photographs. While I can’t go to the theatre and make pictures, I find solace in being able to look through them – as an antidote perhaps. They don’t replace my real-life experiences, but they have become a meditation on creating moments in the dark. Some of the most engaging and evocative images I’ve ever made were shot in a theatre.

For me, photographs have always been comforting. I can lose myself in a photograh. This is part of the reason why I have spent more than a decade making them.

Photographing performance is unique. It’s a dance between so many moving parts: highly technical, physically taxing and historically problematic. It is one of the most exhilarating and nerve-racking of photographic practices, and I’m completely hooked. I witness – through a lens – the incredible act of live performance. When I am commissioned to produce a series of performance photographs, I am engaged as an artist and collaborator, and my pictures will inevitably contribute to how we all think, feel and understand what performance and theatre can be.

It is a privilege to take photographs of performance. I am invited in to make pictures of a performance that has meticulously come together through the vision of the artists involved.

The photographs I produce are still moments from an art that is ephemeral. Photographs of performance cannot recreate the experience. Photography, as Roland Barthes famously notes, is the future death of the subject (1993 [1980]). In a way, to photograph theatre is to kill the essence of the theatre… What remains within the still photographic frame is a moment that was, and is now no longer. Even so, this “death” of the performance moment also provides evidence that it once existed. The photographs point to the temporality of the original event. As Australian academic and editor Gay MacAuley wrote in About Performance (2008), they are “an evocative trace of the absent performance” (p.47).

‘As with any photographs, the more time we spend with them, the more they reveal about themselves. With each return to a photograph, I find it more profound.’

Their main objective is to be documentation. Photographs are used for publicity, reviews, technical information and archival or historical accounts – the reportage of the live event. For me, these uses provide a framework that I negotiate as part of a “brief”. I need to make sure that I have photographs of all the key dramatic moments, or to profile each performer, whether they are an actor, soloist, dancer or an ensemble. These pragmatic concerns fulfil a professional and diligent agreement that I have with the organisations and individuals who employ me. The photographs also become an archive of that performance for future use through extensions of their original purpose and may be used for a range of different outcomes. Academic texts, funding reports, articles and book covers take the photographs out of their first initial audience and provide a new means of circulation and engagement with the photographs and the work.

Performance photographs contribute to a greater cultural understanding of performance through time. They allow us to see the shifts within local and global performances, to learn more about our own bodies of work, and relate to previous performances of the same work done differently. American academic and writer Amelia Jones (1997) speaks from the position as a performance art critic, where the only way she can access and write about performances she hasn’t actually seen is through the photographic documentation. She says that the photograph supplements the performance, and challenge its ontological priority. Writer Phil Auslander extends this idea further, claiming that the “documentation does not simply generate image/statements that describe an autonomous performance and state that it occurred: it produces an event as a performance” (2006, p.5). Auslander’s idea gives weight to the interdependent relationship between the two.

Performance photographs are a valid artistic response in themselves. Just as their value as documentation is acknowledged, I think their creative qualities should be recognised too. A series of performance photographs sit alongside the performance or production. They do not claim to be a performance, nor try to recreate the temporal nature of the experience of being in the theatre. They are an original rendering of dramatic moments, created by one artist in a real-time response to the live performance.

When I step into a theatre, I am a little nervous, excited about what I will experience there. I am wholly aware of the nervous energy from the company too – from director to cast, musicians to creatives, technicians to company staff. Even though I have been invited to photograph the first dress rehearsal, a known quantity in the schedule and a familiar face, I am both inside and outside of the production. My arrival signifies a moment that is concrete – a moment of capture – where the production or performance must “come together”, and my photographic record is a testimony to that show. Ultimately, I am entrusted to distil and memorialise this show as a series of photographs.

The way I photograph theatre has developed over many years, and with each show I learn more. I learn about theatre, lighting, acting, drama, photography and me. When photographing any live performance, you have to know your craft very well, as there is little time to think. The camera or cameras become extensions of yourself. I approach a production photography session like a new audience member, yet without being tied to one singular seat within the dark auditorium.

I have the privilege to move around, and I do, constantly. I am known to run up and down aisles, jump over seats and lie down on the floor. I am theatre fit, ever ready to experience and see something new. I will have not seen the performance beforehand: I like to respond to my initial experience of the piece. I will watch a lot of the performance as I don’t feel like I need to photograph every single moment. I stay curious though, watching, listening, moving and composing each frame to reveal something about the show that I see. There are moments that I will miss, but I don’t mind. I feel this is authentic to an audience experience.

‘Photographs are a major way of re-engaging and thinking through past performances, but they are also a way of visualising broader bodies of artistic work’

I enjoy making decisions in the moment, where a beat within the performance provides me with a creative and instinctual response to photograph that moment. Like Henri Cartier Bresson’s famous “decisive moment”[1], this happens too within the performance; when my photographic instinct collides with the dramatic one provided on stage. I almost always know if I have got “the shot”. It’s a satisfying feeling, but then you’re off again, searching for the next one. The adrenaline rush is addictive, and the feeling of intensely engaging with a performance utterly all-consuming.

My photographs of a performance are the evidence of my experience, of what Barthes would say is evidence of “having-been-there” (1977, p.44): my claim to what I saw and what I was able to create with my camera. As a photographer of performance, I have an extraordinary vantage point of being in different worlds, experiencing a huge range of emotions, and ultimately cementing a fiction in my photographs that are a testament to what I have seen.

After a performance, what grounds me are the results of my labour: the photographs themselves. In each frame, they provide a still moment, chosen from a hundred other moments. What a production photograph portrays is as much up to me as it was to the theatre production at the moment of taking the photograph. It is a series of circumstances that enable that split second to happen. They are moments when the photographer has been able to capture the show’s critical dramatic moment – a decisive moment – where design, acting and photography come together. Inevitably, my artistic rendering of the still moment becomes one of the lasting traces that people will see, now and perhaps in the future, as a record of that performance. These photographs can become definitive of a work of theatre and are collectively kept in the theatre consciousness – providing further insights, agency and dramaturgical legitimacy.

One of the most interesting observations that I have made in the last decade, is that performance photography can be dramaturgical. I have noticed, through long-term collaborative relationships with directors, creatives and companies, that the role of the photographs can influence and engage with the theatre-making process.

Theatre is a collaborative artform, and photography is a collaborative act. Performance photography as dramaturgy is to see the role of photography as dramaturgical within theatre making. It is a visual collaboration between the photographer and the performance makers, where the role of the photographer is to be a visual thinker in the room. Photography can add value to the creative process, providing another lens for the performance to be created within and for, while engaging with other visual references and making new connections.

Dramaturgically I have found that being a photographer within a rehearsal room can be very fruitful; the photographs become a visual diary of sorts, conveying perspectives on rehearsal process, recorded images and notes on linking themes and visual cues. Through photographing process, staging, improvisation or discussion, the photographs provide another ability to re-engage with the making journey. Whether this is done in real time during the rehearsal process, or as a reflective engagement after the rehearsal has finished, the photographed moments provide new access to the material. They can provide a systematic logbook of the decisions and developments as they emerge, or they might fundamentally disrupt the line of engagement, providing new ways of rethinking and refocusing the process.

One production in which I worked as a visual dramaturg was Fraught Outfit’s On the Bodily Education of Young Girls (2013) directed by Adena Jacobs. Working in the rehearsal room as an artistic associate, I used the camera as a way of being part of the making process. As a familiar body within the room (rather than an outside photographer employed to come in for a few hours to give a quick “behind the scenes” snapshot) I was able to witness the raw intimacy of the rehearsals, which in turn enabled me to create images that were equally sensitive, personal and transformative. Throughout the rehearsal, I created a huge body of photographs that were drawn upon to make broader dramaturgical decisions for the production.

In a similar vein, photographing a director’s body of work over a sustained period of time provides another type of visual dramaturgical discourse. Even though each production is different, a field of view is continuously being made and re-made, so that the photographer and director create a visual dialogue that becomes familiar and more refined over time. Visual synergies can be connected between shows, and as a photographer you start to see and read the visual aesthetics that a director will create.

Photographic choices for that director’s works will emerge alongside visual theatre choices, which I would argue become digested by both parties and provide further dramaturgical conversations. This repeats itself with the next production or performance, where a further set of visual investigations, choices and decisions is made, which is then again digested and confirmed, and so forth. What transpires, as with any long-term collaboration, is a shorthand of aesthetics, artistic decisions, dramaturgical styles and visual systems of making that come together between the artistic practitioners.

‘What remains within the still photographic frame is a moment that was, and is now no longer’

In my experience, this type of collaboration can be a formal one, where there is the intention to work together on a show from the outset using photography as part of the process of dramaturgy. My longest collaborations have been with multidisciplinary artist and director Melinda Hetzel and director Adena Jacobs, where the collaborations have been built out of a continued artistic relationship and friendship over a significant amount of time. We share similar tertiary backgrounds that encourage interdisciplinary collaborations, and this type of engagement is natural and intuitive for us.

In other instances, this relationship may be less formal. For example, I have photographed Matt Lutton’s works at the Malthouse Theatre on and off since 2011. Through mutual respect and artistic endeavour, a visual conversation emerges through the photography of each new work and artistic presentation. The works then can be viewed as an exchange of both the director and the photographer’s artistic visual language. In these less formal relationships, the dramaturgical role of photography may not be discussed, yet I think that the engagement is still apparent.

Partly it’s because the photographs are a major way of re-engaging and thinking through past performances, but they are also a way of visualising broader bodies of artistic work. While I acknowledge there is an argument for having work photographed by a range of different perspectives (or photographers), I ultimately think that there is greater value in having a sustained artistic perspective – where a foundation of visual language can be produced and then developed over time. In the end this results in a nuanced and complex marriage of performance and photography.

Finally, I want to return to the photographs themselves. Although they cannot exist without the original performance, they are evocative and captivating pieces of art in their own right. Each photograph provides a still moment, a human experience through performance. Not only do they have the ability to take us back to the original performance, they also establish our experience of viewing the photograph itself. Photography and performance share so many elements within their artforms. I find UK theatre academic Joel Anderson’s idea that theatre and photography have a mutual preoccupation with posing, staging, framing and stillness (2015, p.1) quite affirming. Each artform is a careful articulation of questions, a process of collaboration, and an outcome of distilled moments.

When I look through my website or my archive of photographs, I see the performer and the shows, but what I connect to are human moments: vignettes of our existence, and how we may navigate the world. Performance photographs contain interior landscapes, where still moments are caught in the frame forever.

‘When I step into a theatre, I am a little nervous, excited about what I will experience there’

As with any photographs, the more time we spend with them, the more they reveal about themselves. With each return to a photograph, I find it more profound. I think performance photographs can be likened to the treasured portraits of family and social gatherings, of the special moments we want to remember. Performance photographs are relics in the same way, acting as totems to other worlds, reminding us of past times and people whom may not be here anymore. Yet sadly, we do not display them on a mantelpiece; so many are hidden in archives, on hard-drives, in filing cabinets, or are lost. Performance photographs can disappear over time. As Australian director and lecturer Glen McGillivray laments, a “double disappearance of performance” (2008, p.33) can occur, where the original performance is forgotten and then the photographic evidence of the performance is buried too.

I guess this is why I want to write and talk and share my photographs of theatre and performance. I want them to be more valuable and more accessible, to ultimately provide a deeper engagement with this temporal artform that is important to our culture and our lives. In times like now, when we are not able to gather and perform, when government support is slow or non-existent, and artists are bearing the brunt of being unable to make their work, photographs that can be evidence of who we are and what we do. More than documentation to be archived and forgotten, they are arresting and ever-present.

References

Anderson J, 2015, theatre & photography, Palgrave, London, UK.

Auslander P, 2006, ‘The Performativity of Performance Documentation’, in PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 84, vol.28, no.3, September, p.5.

Barthes R, 1977, “The Rhetoric of the Image,” in Image, Music, Text, trans. S. Heath, Hill and Wang, NY, USA.

Cartier-Bresson, H 1952, The Decisive Moment, Simon and Schuster, New York, US.

Barthes R, 1993 [1980], Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. R. Howard, Vintage, London, UK.

Jones A, 1997, “‘Presence’ in Absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation,” in Art Journal, vol. 56, no. 4, pp.11-18.

MacAuley G, Lohr H, 2008, “A Duet Between Performer and Photographer”, in About Performance, No.8, Australia, pp.47 – 65.

McGillivray G, 2008 “Still Not Seen, The Hidden Archive of Performance,” in About Performance, No.8, Australia, pp.31 – 45.