Playwright Jean Tong talks to theatre makers Rachel Perks and Bridget Balodis about queer dramaturgy and identity, astrology and finding a new language

Theatre artist Rachel Perks and director Bridget Balodis, now working together under the recently-coined banner “Double Water Sign”, have been collaborating since Melbourne Fringe Festival 2014 when they put Angry Sexx out into the world.

I saw Angry Sexx and I still remember the feeling of the show – like bile slowly inching its way up into my throat and collecting there, getting caught, leaving me breathless and with an ugly taste on my tongue. In 2016, Perks and Balodis made the feminist, queer sci-fi epic, Ground Control. I saw that too, and I remember the feeling of lonely desolation settling into my chest.

Which is all to say: when Perks and Balodis asked to be interviewed for their upcoming show, Moral Panic, I jumped at the chance to figure out how they do what they do.

We sat down for an hour-long chat that took us from queer dramaturgy (What is it? How do you do it? Why do you do it?) to queer identity, from making up new words for a new world to the political question of horoscopes (turns out Balodis is a Scorpio-Scorpio and Perks is a Scorpio-Cancer, which is why they call themselves Double Water Sign).

SWOLLOM: THE FEELING OF RAGE POOLING INSIDE YOU

JT: What does queer dramaturgy mean to you?

BB: There’s a very ancient monolithic principle of what good theatre is. What we really want to do is disrupt that for the audience, have them understand that it is intentional, and think about why we might want to disrupt them. I react against patriarchal dramaturgy because I’m not interested in cohesion and completeness and coherency: those things feel like a trap to me. I’m not interested in being a dyke-only or a woman-only. I want more freedom than that, and I find patriarchal dramaturgy to be constricting and constrained.

RP: In Ground Control, I used feeling and intuitive principles as a guiding dramaturgy rather than going A+B=C. Rather than plotting in a traditional sense, I was trying to move an audience through a series of emotions. We try to make every line mean as many things as possible so that everyone in the audience can find something different. We make work for people whose identities sit outside of the centred identity. We want them to feel like their experiences are being represented because their experiences are not being centred.

BB: It’s an explosion of feelings and politics. It’s much more exciting when you have queer people come up and say, “I totally get it” and “that was my experience onstage”, rather than saying “I was right, I decoded your theatre and I found the message”.

JT: The blurb for Moral Panic talks about trying to find your ‘mother tongue’. It’s interesting in relation to the queer community constantly finding new words to describe new intersections of sexual and gender identity. Do you explore that in Moral Panic?

BB: There’s a kind of anti-label kind of sentiment in the work, a desire not to explicitly define and not to explicitly name sexuality. It’s interested in the queerness in the relationship between sex and the body and desire. Those things are blurry and the work wants to be in that blurry place.

RP: Something that is fundamental to my experience of queerness is confusion, and maybe that’s not something that I have to pass through to get to an endgame and maybe it just is confusing. Maybe that’s okay, because it’s complex and nuanced and we don’t have structures within our language that can represent it without simplifying it. The work also looks at the way that queer folk and femme folk are often the centre of the evolution of language. We spent a whole day workshopping words for things we didn’t have the words for.

BB: We call them “slinnetses”, which are words for things we didn’t have language for.

RP: Traditional patriarchal language breaks down in the mouths of characters because it’s not for us – it’s built to describe and centre a different experience than the one we have, so where do we go and find another point of origin?

SLINNETSES: A WORD MEANING ‘I DO NOT HAVE A WORD FOR THIS EXPERIENCE’

JT: So where do we go? How does developing writing through a queer dramaturgy differ from working through a dominant, patriarchal lens?

BB: It’s so rare for like femme people to hear, “I understand completely, let’s do it”, instead of “this could be better or different” or “you’re nearly there”. It’s important in a critical sense as well. If you’re not getting institutional validation—and very few people who work in theatre do—then you need to find it somehow, you need to find the thing that’s like, “Hey, this thing that you’re doing is deliberate and intentional and fucking interesting and exciting and necessary”.

RP: It is something deeply considered to be working in a reactionary place. I think about writing a play as pulling something out of yourself, and sometimes you pull things out of yourself and you’re like, “oh my god, it’s just me, that’s just my thing I’ve pulled out of myself”, and sometimes you pull it out and you go, “oh no, it’s kind of copying a thing”, or “that’s being safe”. I think the longer that we work together, the closer I get to pulling out something that’s just me, that’s just us and leaving the other stuff behind. In the writing of it, the way that I know when it’s done is when everything in the play is now complicated.

BB: In terms of the dramaturgical process, Emma Valente’s working with us on Moral Panic, and she brings questions that give you some sense of how to classify what you’ve made and then strengthens that, rather than trying to make something fit into the pre-existing structure.

RP: I worked with Daniel Schlusser on Ground Control as dramaturg and then Emma on this one, and I thought that dramaturgy was being the person who went, “so, this act doesn’t drive up until the climax”, or, “this comes out in the end but that’s not served in the beginning”, that sort of technical stuff. And my experience of working with Emma and Daniel could not be more different. They go, “This bit feels scared” or like –

BB: “Have you thought about computer games?”

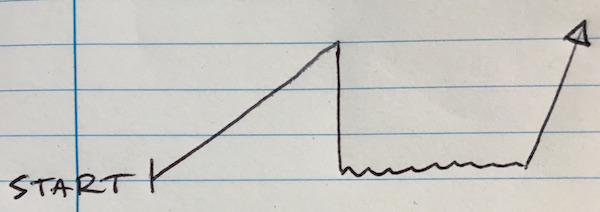

RP: Daniel said, “I think you should watch Tekken”. Once at a meeting with Emma, I drew this line drawing to represent the structure of Moral Panic and about six months ago when I started feeling like the play was done, Emma was like, “it’s like the drawing you made”, and I was like, “great, I’m done”.

JT: Bridget, what are some of your approaches to queer dramaturgy in your directing?

BB: I start by hunting down the right feeling and the right sound of it. I use a lot of improvisation and abstraction. I do usually the first read at the table and then we’re up on Day One, because I’m looking for the feeling of it – if I get the actors up and moving, then all I’m looking for is the physical relationships. I get really excited about really minute stuff. I get them to do whatever they want, and then I’ll stop them and say, “Wait, what you did with your hand there, I want to see that again. And again. And again”. I’ll be totally released of control, sit well back, and then I’ll zoom in on something very particular that I’m into, or an action that happens that has an emotional effect.

RP: You direct in quite an egoless way, which is quite non-normative.

BB: I think that’s how any director of new work should direct. That’s my job, to represent the script in its truest version on its first outing in the world. We’ve also got an all femme or non-binary cast and it’s important to us in terms of making space where the male gaze isn’t allowed.

RP: Even if that’s not coming from the [man], we’ve lived in this world long enough for us to be projecting onto that person. Like if there’s a man in the room then you’re going to be like “oh, he probably thinks I’m not doing a good job”.

BB: Even if he’s not, it still changes the space.

SANSKA: THE STAIN LEFT ON THE BODY AND MIND BY VIOLENCE

JT: That zooming in on details makes me think about queer communities using very minute details to signal queerness in a world that’s very straight.

BB: That’s exactly right. It’s to do with the physical and the external and the haircuts and handkerchiefs and clothes and shoes. How you walk, how you talk –

RP: It’s energetic. You can feel when someone has a queer vibe, it’s a physical thing.

JT: How do queer vibes play out in Moral Panic?

RP: I was watching Killing Eve, what I love is that the tone is so unpredictable. One moment you’re in a high drama action scene, the next moment it’s a fart joke, and the next moment someone’s killing someone. It puts you in a space where you’re like really constantly having to be on the front foot as an audience member –

BB: – and moderate your response. That feeling is one of the most satisfying things to do in theatre as well, to have the audience laughing uproariously and then be like, “fuck”. Queer folk are constantly moderating our output in the world: how am I being read, is it safe for me to be read in this way right now, do I need to change what I’m doing so that I’m safe?

RP: Replicating that tonal shift in the play is a way of being outrageous without having extreme violence or extreme sexual content. You can be outrageous and confrontational just by keeping your audience in an unexpected place.

SUSKENDENDER: A STATE OF FOCUS SO COMPLETE YOU FORGET YOURSELF AND YOUR PHYSICAL FORM

JT: In speaking about queer and femme bodies, I think we’re reaching an interesting point, particularly in queer discussions surrounding masculinity. Do we deal with the possibility of a non–toxic masculinity in Moral Panic?

RP: The character that Kai will be playing, Andy, is non-binary. That character is kind of me looking at my own struggle with gender, and with being uncomfortable with the androgyny inherent within me, and wanting to reject the masculinity of it. It’s about fighting for so long against something and realising it’s in you. I think there’s been a really interesting discussion in the butch community that’s about how being butch or androgynous is not about wanting to be a cis-man. It’s about embracing the multiplicity of your own energy and your own identity.

BB: I think that that’s what’s so exciting about what’s happening with the trans community choosing not to participate in a binary is really exciting in terms of power. It’s like, “hey, if I refuse to participate in the binary then what I’m doing is disempower the patriarchy. I’m not choosing to be either the oppressor or oppressed. I’m out”. It’s going to be something else.

JT: You were talking about astrology before, and it really feels like queerness and astrology have collided in the last two years. Why do you think that is?

BB: I think it’s an aversion to current political systems of government and systems of finding meaning. It’s about going, “I don’t believe in it anymore, I’m going to believe in something else altogether”. What’s happening in parts of the world to queer communities is scary, so I think it’s a way of opting out.

RP: I’m writing for screen at the moment about a character who’s coming out. She’s decided to spend a week living her life directly according to her horoscope and she describes it as living her life more authentically by using astrology as an overtly un-patriarchal system of life-navigation. I use that as a joke, but I think that is my life.

BB: There are people in the community who are completely and seriously invested, but I think there’s also quite a camp kind of appreciation for it as well. And that’s allowed – to post memes about Scorpios and simultaneously being genuinely invested in it.

RP: There’s something about the irony of where we’re at in comedy at the moment with that millennial meme culture – everything is serious and everything is also not serious.

BB: Who decided that the system that we have is actually the best one?

JT: Coming back to taboo elements of interests associated with femme interests (astrology, witchcraft, etc), was there a specific moment that pushed you to write about the phenomenon of moral panic?

RP: There’s something that’s really scary about feminine people, about women and non-binary femmes, and really all queer and trans people. It’s seen as deviant. I wanted to make a play about all of the things that are scary about that. Basically, if you’re all really scared of that, then that’s where I want to be. That’s what I want to make a play about. I would rather be scary than be scared.

LOOMBRA: EMPATHETIC INTUITION, UNDERSTANDING OR FORESEEING OTHER PEOPLE‘S FEELINGS BEFORE THEY EVEN KNOW THEM THEMSELVES.

JT: What is your favourite feeling in the play?

RP: Audacity has always been my favourite thing, where I laugh at what I wrote out loud because I can’t believe I’ve been so naughty.

BB: My favourite is the feeling of power in a femme body. There’s a very powerful monologue at the end of the play, and it’s exciting to see that level of leadership and actual power.

JT: Are you using any spells or rituals that are real?

RP: There’s one passage that I lifted off Tumblr. Most of it I wrote myself. There’s these strange chants that happen throughout the play where the characters lift into like a different sort of liminal time-space. We call them “warps”. The play proposes that queerness and femininity are akin to magic. It’s what I think all of the men are so afraid of, that all these queer bodied and feminine bodied people are actually already magical people.

During the development with the creative team after the interview, Perks and Balodis are simultaneously uproariously silly and professionally attentive. The team’s banter swings between deeply ironic and perfectly sincere.

Balodis gets the design team to answer questions about what shape the play is, what substance, what food, what smell. Perks cackles about quiche; Balodis interrupts the pondering to say, “I’ve had to think about it for too long”, reminding everyone to go with their instincts, their gut feelings about the feel of the work.

There’s something wonderful and terrible in the tone of the way they work with each other, something light and dark at the same time, something rough and slick at the same time, something queer, something everything and multiple and all at once.

Moral Panic opens at Northcote Town Hall Arts Centre on November 14.

3 comments

Loved this peek into the culture of this particular creative space and collaborative process. Thank you.

[…] articles I read: ‘The Dramaturgy of Queer‘ with Jean Tong interviewing Bridget Balodis and Rachel Perks for Witness, talking about […]

Please cf. Cixous and Clément’s ‘The Newly Born Woman’.

Comments are closed.