‘It feels like the same old exploitations, enacted now in the name of art’: Alison Croggon on Milo Rau’s La Reprise

Content warning: racist and homophobic violence

Swiss director Milo Rau has been called “the most controversial theatre director of his generation”. It’s not hard to see why. For a start, his company, which he founded in 2007, is called the International Institute of Political Murder (IIPM), and makes what he calls a “sociological” theatre that, as its name suggests, investigates political violence.

Its first production, The Last Days of the Ceaușescus, investigated the trial and execution of Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife when the Romanian Communist regime collapsed in 1989. When Rau became artistic director of NTGent, he decided to make a show about the Ghent altarpiece and, two years after the Brussels terror attacks, advertised for IS jihadis to audition for roles as Crusaders. He’s made theatre about the war in Congo and a piece about the Belgian paedophile murderer Marc Dutroux that used child actors.

And, as La Reprise at the Adelaide Festival makes clear, Rau is an extremely intelligent theatre maker. La Reprise is a genuinely traumatising show, carefully building up alternating layers of artifice and authenticity in order to recreate a shocking crime that illustrates what Rau calls the banality of evil, presumably echoing Arendt (I’m unsure if the translation actually chimes)

I walked out feeling deeply shaken. This is beautifully made theatre, no question; it’s well polished and remarkably accomplished. But there’s something wrong, bang in the middle of it; a sense of a predatory intellect that left me interrogating its entire premise. I still don’t understand why it was necessary to make it.

La Reprise premiered last year, and is Rau’s first show determined by the so-called “Ghent Manifesto”, 10 rules that he says all shows under his artistic direction must follow. “The aim,” says Rule One, “is not to depict the real, but to make the representation itself real.” To this end, La Reprise carefully reconstructs the April 2012 murder of a gay man of Moroccan origin, Ihsane Jarfi, in the post-industrial Belgian city of Liège.

As per other rules of the manifesto, it is performed in two languages, French and Walloons (with English subtitles), and as well as its professional actors – Kristien De Proost, Sébastien Foucault and Sabri Saad el Hamus – the show includes several non-professional performers, Fabian Leenders, Tom Adjibi and Suzy Cocco, whom we first see being auditioned for their roles.

The whole project calls up inevitable echoes of Moises Kaufman’s The Laramie Project. Ihsane Jarfi’s murder is very similar to that of Matthew Shepard – a brutal, senseless beating of a gay man who is left to die – and so are the genealogy and form of the two works. Both are deeply informed by The Street Scene, in which Brecht outlines his idea of Epic Theatre as “an eyewitness demonstrating to a collection of people how a traffic accident took place” in order to create “a social enterprise whose origins, means and ends are practical and earthly”.

The text is devised by Rau and his collaborators, who also, as with The Laramie Project, reveal their research process and personal investments in both the performance and the crime, creating a work of theatre that interrogates real events from multiple perspectives. And there the resemblance ends.

The intention of The Laramie Project – to investigate the causes and effects of a terrible crime in a rural community – was very clear. La Reprise seems, in contrast, not clear at all. It is, primarily, an investigation into theatre – it begins and ends with questions about what it means to mount and complete a work of performance. And the murder of Jarfi seems more the occasion for this investigation than its reason: a conveniently dramatic real event that can spectacularly demonstrate the capacities of theatre.

As with The Last Great Hunt’s Lé Nør at the Perth Festival, it creates a filmed reality that is constructed before our eyes. Some of the footage is videoed live: some, in perhaps the most effective parts of the show, is pre-recorded, filling the realities depicted on stage – a man miming walking a dog, for instance – with the missing bodies. It fills the theatre with absences, an almost palpable summoning of ghosts.

Anton Lukas’ set is a working space, with two tables and various chairs placed diagonally on either side of the stage, a big screen centre stage, a cameraman moving around the space as a kind of silent conductor of the performance. We are simultaneously told what happened to Jarfi and how the cast are making the play: Adjibi, for instance, who plays Jarfi, is asked what his favourite music is, and he names Purcell’s The Cold Song – “Let me, let me, let me / Freeze again to death” – which, in a considerable coup de théâtre, he sings at the very end of the show.

Following our introduction to the performers and the premise of the production are five chapters, echoing a five act play, that investigate different aspects of the crime. One is a reflection on one of the murderers by Fabian Leenders, for instance, who as a working class man from Liège has a very similar biography, down to the childhood death of his mother; another, very moving scene, sees Sabri Saad el Hamus and Suzy Coco, both naked on stage, playing Jarfi’s parents in the days before he went missing and after he was found. The whole culminates in the crime’s reconstruction before our eyes.

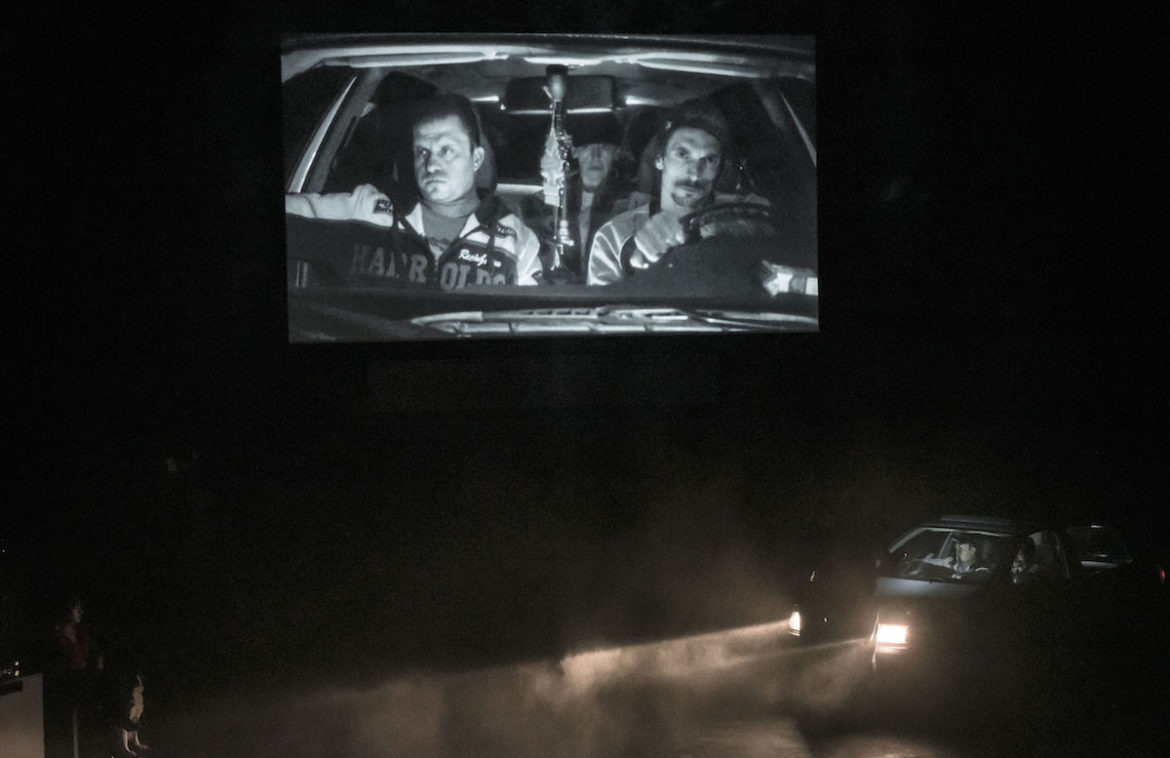

This chapter, which if I recall correctly is called The Banality of Evil, is the climax of the show, and is unambiguously traumatising. It unfolds agonisingly over durational time. We see Jarfi get into the car with three men, we see them begin to beat him up, we see him praying, we see them drag him out of the car, strip him naked, kick him to death, and leave him, unconscious, to die slowly of his injuries and exposure in the rain.

And I find myself thinking about the US conceptual poet Kenny Goldsmith and the shit that went down in 2015 when he read a slightly reworked version of the autopsy of Michael Brown as a conceptual performance. Michael Brown was the Black teenager whose fatal shooting at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri, sparked the Black Lives Matter movement the year before.

“The Murdered Body of Mike Brown’s Medical Report is not our poetry, it’s the building blocks of white supremacy, a miscreant DNA infecting everyone in the world,” said an anonymous group called the Mongrel Coalition during the scandal. “We refuse to let it be made ‘literary’. Goldsmith cannot differentiate between White Supremacy and Poetry. In fact, for so many the two are one and the same.”

At the end of La Reprise, my body and psyche vibrate with the trauma of the violence: it overshadows every other response. And I can’t but wonder why Rau felt that re-enacting the crime adds anything to our understanding. There’s a suggestion of a reason in some comments from Jarfi’s former lover, who speaks of remaining in the courtroom to see Jarfi’s murdered body because he didn’t want him to be alone, to be abandoned in his death. He speaks of wanting to understand Jarfi’s anguish, needing to enter it so he might be closer to him. And that might indeed be part of processing the cruel, pointless death of a loved one.

For us, as audience members who don’t know Jarfi, it feels different. I recall the force of the Mongrel Coalition’s objections to Goldsmith’s appropriation of another’s suffering, its critique of the spectacle that racist, colonial ideologies make of violence against subjected bodies. Why should this act be aestheticised? To what end? To show us that theatre can do this, that theatre can be this powerful? What do we understand, besides the natural shock and revulsion against such a crime?

The truth is, not much. We understand a little about how the loss of a loved human being reverberates through a community (though you have to google to discover that Jarfi’s parents created a foundation in his name to fight against homophobia). We don’t understand why the crime happened, and we understand almost nothing about his murderers, except that they are unemployed white men in a city that has fallen on hard times. Even this, the fall-out of the collapse of late capitalism, is skipped over: the “banality of evil” doesn’t cover it. Bizarrely, although the suffering body is real, the murderers themselves are not. Unlike The Laramie Project, we come away with almost no knowledge of the community in which this crime took place.

I think what we really understand is that this violence is enacted on queer bodies, on brown and black bodies, and that we, as inheritors of patriarchal European colonialism, have the power to inflict it again. The representation on stage is not, as the Ghent Manifesto claims it should be, “real”, although my visceral responses were real enough. We are given a voyeuristic glimpse of violence that begins and ends in the closed world of theatre, that in the end serves mainly to aggrandise the power of theatre itself.

The aim, says Rau, is “not just about portraying the world. It’s about changing it.” But this, no matter how artfully done – and it is achieved with remarkable artistry – doesn’t feel like change. It feels like the same old exploitations, enacted now in the name of art.

La Reprise. Histoire(s) du théâtre (1), concept, text and director Milo Rau. Research and dramaturgy Eva-Maria Bertschy, Stefan Bläske, Carmen Hornbostel, François Pacco. Design by Nina Wolters, set and costume design by Anton Lukas, video by Maxime Jennes and Dimitri Petrovic, lighting design by Jurgen Kolb. Performed by Kristien De Proost, Suzy Cocco, Sébastien Foucault, Sabri Saad el Hamus, Fabian Leenders and Tom Adjibi. The International Institute of Political Murder (IIPM), Création Studio Théâtre National Wallonie-Bruxelles,Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival. Closed.

2 comments

Thank you, Alison. You have articulated my concerns in regard to this production. Yes – extremely well done, but I found it ultimately rather repellent and questionable. It was not intended as ‘good night in the theatre’ and it most certainly wasn’t as far as I’m concerned. As a gay activist I don’t need to be lectured or subjected to overwhelming violence against other gay men and women. Nor do I believe, perhaps naively, perhaps hopefully, that others in the audience need such a violent production to highlight this matter. Subsequently, I did focus on how this message was being convayed. I don’t get all the nudity – what was all that about? I also question the graphic detail. They want it to be ‘real’, but within a theatrical environment. These worked as binary opposites to me and difficult to reconcile. I’m reminded on what The Player says in Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead – how a ‘real’ execution doesn’t work, it doesn’t bring in the audience, whilst a ‘theatrical’ execution always works because it plays on the imagination. There wasn’t much left to one’s immagination in this violent show.

I suppose…the reality of that violence, that we see constructed in front of us, says something about how violence is constructed and represented? But yeah, for me it just said that we have the power to construct this violence, whether it’s real or imagined. It’s interesting how that violence for me obliterated everything else in the rest of the show…there were moments that were tender and gentle, after all.

Comments are closed.