Perth Festival Diary #2: Barber Shop Chronicles and Farewell to Paper

Masculinity. It’s the water we all swim in, whether we’re aware of it or not, whether we resist it or accept it, whether we’re men or women or neither. It’s so dominant that most of us scarcely notice how it structures our lives.

Masculinity is still, even in the era of #metoo, even after more than a century of feminism and anti-colonialism, the default standard of what it means to be human. European literature, our art, our social and political structures, have been defined by a particular masculinity – white, mostly heterosexual, middle or upper class – for centuries. This masculinity performs itself for us on all our cultural stages: it tells us its tragedies, celebrates itself, mourns itself, defines itself. Yet it seldom interrogates its assumption that it is the centre, that its pronoun, “he”, is a sufficient indicator for all humanity.

When masculinity is questioned, it’s most often through the lens of those who find themselves defined most constrictively in its hierarchies: women, queer people, men who are Jewish or African or Muslim. Inua Ellams’ play Barber Shop Chronicles is an example: at its core, it’s a bleakly honest play about masculinity. More specifically, it’s about how the selves and lives of black African men have been distorted and wounded by European colonisation.

That’s a huge subject, and Ellams, a Nigerian-born British poet, playwright, performer, graphic artist and designer, doesn’t shy away from its complexity: one of the difficulties in writing about this show is how many rabbits it sets running. He puts masculinity under a critical lens that is usually applied to notions of femininity: it’s as troubled, as permeable, as contingent and often as damaging. And it shows that, just as femininity is a concept applied to female bodies, usually to their detriment, so masculinity shapes and hurts real male bodies.

Crucially, and not uncoincidentally, Barber Shop Chronicles is also superb theatre. From the moment you enter the auditorium, the space is electric. The stage is full of audience members: a few in barber chairs, getting a free haircut; a bunch of young people pulled onto the floor by cast members to dance. The transition from enthusiastic audience participation to front-on play is seamless, seemingly effortless, as is every shift in this virtuosic production. Audience members saunter to their seats as the cast gathers in a knot front stage, and then the lights focus with a snap and the actors are cheering a televised soccer match, barracking with such conviction that I keep looking over my shoulder to see what’s happening on the imaginary screen.

This production achieves the holy grail of theatre: text, direction, design and performances all working in perfect (sometimes literal) harmony, each illuminating the others. Bijan Sheibani’s direction is constantly inventive, pulling together a complex unity with an unerring eye for the choreography of bodies. Jack Knowles and Rae Smith’s lighting and stage provide the perfect frame for this text: simple, fluid and expressive. You laugh almost all the way through, and walk out feeling buoyant and alive.

Ellams’ text is written with a poet’s ear and a performer’s intuition for theatre, and plays across the variousness of African dialects and languages within Africa, as well as the wider diaspora. It is unapologetically and consciously about men, its complexities striking against the degraded or monstrous images of the black man that haunt the colonialist gaze.

Sometimes these characters are drunk, or bigoted, or deeply, bitterly angry; but they are also gentle, compassionate, funny and wise. Which is to say, they are presented as complex, fully-realised human beings, subjects of their own experience. Although women are discussed in different ways (some troubling, some not), in this play the absence of women registers most powerfully as grief.

The concept is simple: the entire play consists of conversations between men in barber shops in Lagos, London, Accra, Kampala, Johannesburg and Harare over the course of a single day. There are several loosely interwoven stories, but the narrative spine occurs in the Three Kings barber shop in Peckham, London, where a young barber, Samuel (Bayo Gbadamosi) simmers with resentment against the shop owner Emmanuel (Cyril Nri). Emmanuel is a former partner of Samuel’s father, and Samuel believes that he cheated his father out of the shop.

The conversations and arguments range widely, but all of them devolve on the material and psychic consequences of colonialism. There’s an argument about the decline of Pidgin English as a common tongue across Africa, which reminds us how language was as much a tool of colonisation as armies. There’s aggressive questioning of the Western deification of Nelson Mandela, attitudes to homosexuality in Uganda, commentary on Zimbabwean politics. A confronting moment when a South African man confesses that he charged his white schoolfriends to call him the insult “kaffir”, a humiliation driven by the larger humiliations of poverty.

Using some clever repetitions and linking – a joke that keeps returning, the soccer match between Barcelona and Chelsea FC – the theme of paternal betrayal and absence ripples out through the various stories as a question: what does it mean to be “a strong black man”? This question is never answered: instead it resonates further (what does it mean to be a man? a woman? a human being?)

It’s impossible to imagine a better cast, a dozen remarkable actors playing 30 characters. There isn’t one missed beat: every actor knows exactly where he is and what he’s doing. It’s some of the best ensemble acting I’ve ever seen, so it’s impossible and kind of unfair to pick out highlights: but Cyril Nri broke my heart. If you missed it, I’m sorry.

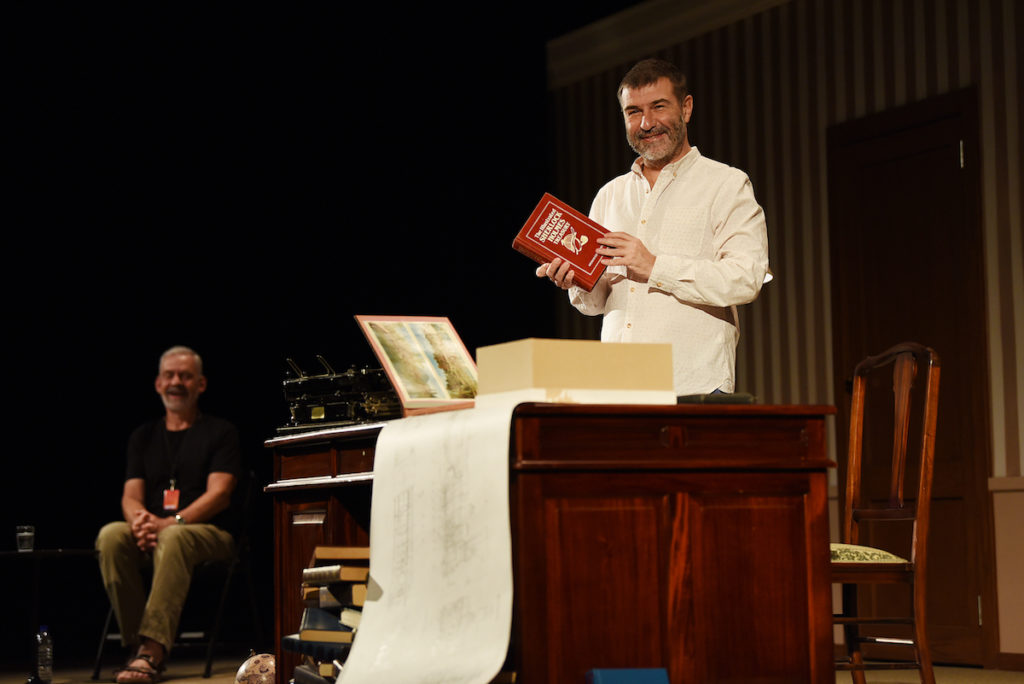

Kyle Wilson (right) and Evgeny Grishkovets in Farewell to Paper. Photo: Toni Wilkinson

Like Inua Ellams, Yevgeny Ghrishkovets is a poet and performer. His show Farewell to Paper is almost the polar opposite of Barber Shop Chronicles. It’s effectively a monologue (spoken in Russian, with the heroic and sensitive Kyle Wilson working as live interpreter) which, as its title suggests, is an elegy to the passing of paper in the digital age.

Ghrishkovets seems to be a Russian equivalent of Clive James, a popular raconteur with a self-deprecating charm that appears to be a cover for a robust ego. Two hours is a long time for a monologue: presumably in the original form, without interpreting, it would have been around an hour, which would have changed the experience considerably. And while Barber Shop Chronicles uses its two hours’ duration to range restlessly over specifically targeted but vast speculations, Ghrishkovets subjects us to his personal obsessions.

Not that there’s anything wrong with one’s own obsessions: much magnificent art is driven by such singularity. Ghrishkovets has a disarming line in intimate recollection, which he then uses as a platform to leap to outrageous – and erroneous – generalisation. This meant that I spent a lot of time mentally arguing with the show.

Yes, of course it is true that we are moving away from the relative permanence of paper to the instability of pixels. No, it doesn’t mean the end of books, or even that no one buys books any more, or that people are forgetting things, or that people don’t handwrite. If anything, handwriting is fetishised. Notebooks are more popular than ever: sales of Moleskines, for example, more than doubled between 2010 and 2015, and most customers were under 35.

And yes, we don’t write letters any more. I used to be an indefatigable correspondent. It was a wonderful thing, and like Ghrishkovets I regret the lost, slow pleasures of the post. But no, not every school exercise book in the world in the ’60s (I am about the same age as Ghrishkovets) had blotting paper: certainly not ours. Yes, I remember those desks with empty inkwells, but I never chewed up blotting paper and blew it through tubes, because I was a girl. And so on.

Human beings will always make meaning, with whatever materials they have to hand. Which is what Ghrishkovets is saying. Or is he? In the circularity of his argument, which winds back and forth through his nostalgia for 20th century objects like post office boxes and typwriters and telegrams, I wasn’t sure. It did make me think of the things that are gone or going forever, and which he didn’t mention: the natural world as we know it, for example, as we face the fifth major extinction event in the history of this planet.

The longer the show went on, the more annoyed I became. I felt irritated by Ghrishkovets’ assumption that my time – most consciously won, as he pointed out in his metatheatrical prologue at the beginning of the show – was worthy of this rambling and ultimately banal theatrical lecture. By the end of the show I had identified the actual source of my oscillating boredom: it was his constant blithe assumption of his universality, of himself as the point of reference. It’s that very familiar assumption of unimpeachable subjecthood that underlies all masculine literary privilege.

It wasn’t a surprise to google Ghrishkovets afterwards and discover that his stories are intentionally attempts at the “universal”. Of his first show, How I Ate a Dog, he remarked “I had one goal: simply to offer the audience the chance to rejoice in the fact that we live a universal life – at least during childhood and our youth.” Not a modest goal, then.

It’s the same old same old: the subject constructed as masculine that plonks itself comfortably in front of us, certain that it will be recognised, and noted, and unchallenged. It performs its doubt, because uncertainty can be seductive: but underneath, there is no doubt of its centrality. Perhaps it seemed particularly insupportable because I had just seen Barber Shop Chronicles, which enacts real doubt, but as the time wore on – and on – I just wanted to scream.

And then there’d be a deprecating little joke, or some sweet memory, and I’d feel that I was just being mean, just over-reacting. Because this is how these things work.

Of course, Ghrishkovets is doing most of this on purpose: his transgressions on his audience’s patience is a conscious reminder of the boredom which we have forgone in the age of instant gratification; his anti-spectacle, with the odd miserly theatrical effect (in keeping with its metatheatricality, always pointed out) militates against our craving for diversion. But I’m not sure about the masculine entitlement: that seemed to be presented unironically, without interrogation.

Farewell to Paper is presented as a show about mortality and finitude, but I only felt it as sentimental nostalgia. It’s not so much a meditation about technological obsolescence as the expression of a yearning for the universal “he” that stands in for all humanity (and erases all other kinds of experience). It’s masculinity sneaking back into the centre of the stage where it knows it belongs, shrugging its shoulders disarmingly, telling “us” that things are as simple as “we” hope, and that “we” never really have to bother with the strange or the unfamiliar or the different. Thank goodness for that.

Barber Shop Chronicles by Inua Ellam, directed by Bijan Sheibani. Design by Rae Smith, lighting by Jack Knowles, movement by Aline David, sound design by Gareth Fry, musical direction by Michael Henry. With David Ajao, Peter Bankole, Twain Barrett, Maynard Eziashi, Bayo Gbadamosi, Martins Imhangbe, Patrice Naiambana, Cyril Nri, Kwami Odoom, Sule Rimi, Abdul Salis and David Webber. Fuel, National Theatre and West Yorkshire Playhouse, Octagon Theatre. Perth Festival. Closed.

Farewell to Paper, written and performed by Evgeny Grishkovets. Translator & Live Interpreter Kyle Wilson. Lighting by Konstantin Vyuev, sound by Aleksandra Viueva. Heath Ledger Theatre, Perth Festival. Closed.

Alison Croggon flew to Perth as a guest of the Perth Festival