‘The whole production looks like an attack on heteronormative patriarchy, dressed up as a surreal and charming fairytale’: Alison Croggon on Barrie Kosky and 1927’s The Magic Flute

The Magic Flute. What do we do with The Magic Flute? Arguably Mozart’s most brilliant opera, it’s certainly his most performed – in fact, as Barrie Kosky points out, it’s the most performed of any German-language opera, and one of the top ten in the world. But oh my. It’s all the problems of the European canon rolled into a single artwork.

The music is Mozart at his irresistible best. The Magic Flute is studded with famous passages, notably the famous coloratura soprano of the Queen of the Night, which remains a sublime and still surprising moment. As I sat listening to the hurrying rhythms of the overture, which unlike conventional overtures isn’t an introduction to themes which will be explored further in the opera proper but an autonomous piece of music, I remembered that one of the reasons art exists is to delight.

Delight and pleasure are often considered secondary things, accidental effects of art rather than its purpose. Sometimes pleasure and delight are considered signs of a lack of proper seriousness (one of my least favourite phrases is “guilty pleasures”), betraying how poorly our moralistic culture understands either of them, how our notions of what they are remain starkly truncated, roped to impoverished consumerist ideologies. But they are among the best things about being alive.

Kosky’s collaboration on The Magic Flute with co-director Suzanne Andrade and Paul Barritt of 1927 is in many ways a match made in heaven. I last saw 1927, a company which subversively and beautifully combines animation and theatre, in 2010, when they premiered their show The Animals and Children Took to the Streets at the Malthouse Theatre. In that show, the fairytale qualities of their animation permitted them to relate an especially dark parable of oppression.

The same thing happens with this production of The Magic Flute, which heads to the Adelaide Festival after its Australian premiere in Perth. It’s perhaps the clearest, and therefore bleakest, interpretation that I’ve seen. Emanuel Schikanader’s libretto, with its heavy use of Masonic symbolism, is often spoken of as a celebration of Enlightenment values, in which reason and moral fortitude lead the soul to the enlightenment of pure love. This production merrily opens up the arcane symbolism into a chaotic fantasia. In doing so, it shows that the Enlightenment, far from being a sober precursor to rational modernity, was completely batshit.

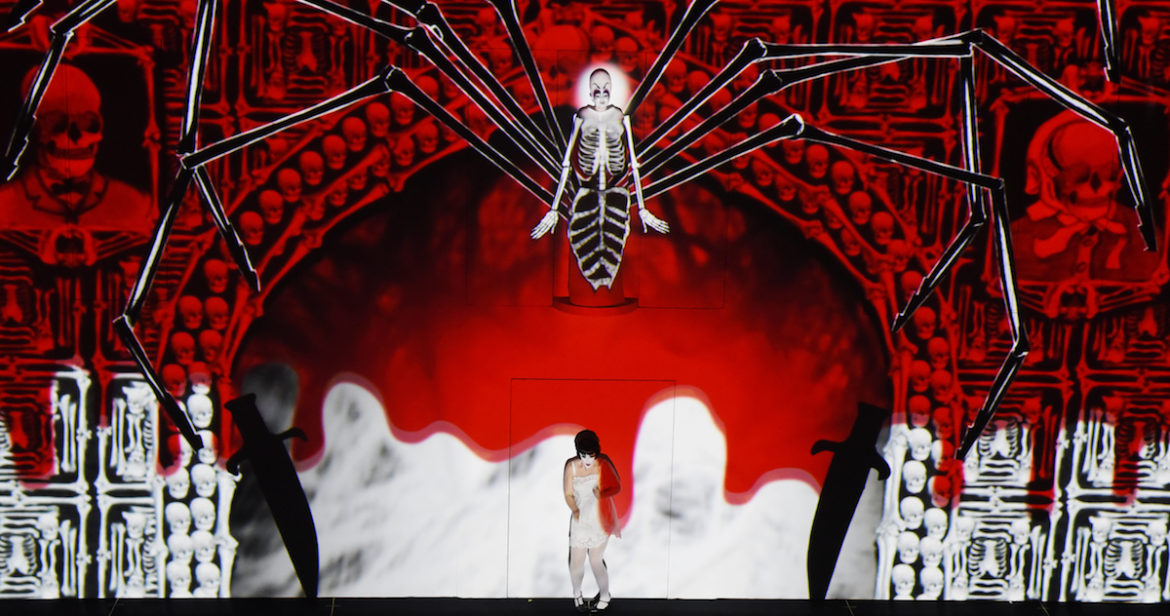

This Magic Flute exploits the imagery of silent films, vaudeville, music hall and other “vulgar” forms. Papageno (on the night I saw it, Joan Martín-Royo) recalls Buster Keaton, in a mustard-coloured suit; Monostatos (Ivan Tursic) is Nosferatu, and Pamina (Iwona Sobotka) is Louise Brooks, in her Lulu role. The dialogues aren’t spoken: they given us as silent film captions, accompanied by keyboard solos. The Queen of the Night (Christina Poulitsi) is a giant Louise Bourgeois spider with knives for legs and a skeletal body: Death herself. The whole plays out over a two-dimensional set, in which the singers interact with a dizzyingly inventive animated world.

Paul Barritt’s animation provokes constant ripples of laughter from the audience, from the moment that Tamino (Aaron Blake) first appears in a dark forest, fleeing a giant orange snake. Although his body is still, his animated legs are absurdly running. When the three ladies (Ashley Milanese, Karolina Gumos and Nadine Weissman) appear to rescue him, they are perched high above on a narrow platform, and their silver arrows hotly pursue the snake across the stage.

The nonsensical story follows the story of Tamino and Pamina, who fall in love before they meet and face complications due to the conflict between the Queen of the Night and Sarastro (Insung Sim), respectively the male and female principles governing this bizarre fantasy. It’s a story about initiation, drawing on some very arcane sources. Kosky says he’s not interested in the Masonic symbology, but he and his collaborators sure make use of it in the wild images that populate the stage. I suspect that Kosky is in fact drawing on the Kabbalah and alchemical symbols, both of which have much in common with Freemasonary.

Certainly, the idea of lovers as a symbol for the struggle of the soul toward enlightenment is an ancient one. Pamina and Tamino, as their rhymed names indicate, are both aspects of the self. The romance of their trials as they struggle through despair towards true love is the struggle of the soul towards enlightenment. And, through the logic of enlightenment, that means that the soul must be rid of the darker elements that bedevil it.

The demons include the usual suspects – women and black people. Tamino is constantly warned to be on guard against the trivial gossip of women, and the Queen of the Night is exposed as an evil, deathly, deceptive influence. Pamina is threatened by the lust of Monostatos, who is explicitly black (though there’s a tiny bit of nuance here: Monostatos has an aria in which he laments his loneliness). There’s not much that can be done to finesse the racism and sexism at the heart of this opera, but I don’t think I’ve seen it so clearly elucidated before.

Sarastro, the patriarch in the temple, is costumed in a Victorian suit and top hat, rather like evil capitalists in classic Communist propaganda, which wouldn’t be a surprising allusion given 1927’s use of Rodchenko’s imagery in The Animals and Children Took to the Streets. He is certainly a sinister figure: one of the more disturbing scenes sees Pamina, crouched in a yellow frame to the right of the stage, surrounded by blinking eyes staring at her through holes in the wall (an image echoing a scene Orson Welles’ film of The Trial). A crowd of Sarastro-clones in top hats and frock coats surround her until she vanishes behind them, and withdraw to reveal her newly dressed in Victorian mourning clothes. This scene is unambiguously menacing, thick with sexual threat.

The chaos of the imagery constantly subverts the text. The temple of reason, art and work is shown to be a nightmare tyranny: Sarastro is lauded by parades of machine-animal hybrids, including mechanical monkey soldiers that uncomfortably echo images propagated by colonial Europe. Pamina, Tamino and Papageno are imprisoned, threatened with death, their bodies injected with strange fluids to prepare them for the trials, and treated with unreasoning sadism.

And they’re deluged with propaganda about how the only true love is between man and woman. Papageno, as the figure of a simple man uninterested in attaining higher things, gets his Papagena (Talya Lieberman), and together they fulfil their function of populating the world with workers. By the time the two lovers finally kiss at the end, their triumphant union comes with an ironic sting.

The whole production, in fact, begins to look like an attack on heteronormative patriarchy, dressed up as a surreal and charming fairytale. Kosky and Andrade’s embrace of its non-sense is a reminder that, as I said earlier, the Enlightenment was batshit, its foundational thought interwoven with the brutal irrationalities that underwrote the colonial ambitions of imperial Europe.

After all, while Newton laid the foundations of modern physics, he was more interested in alchemy and the occult, searching for the wisdom of the ancients: John Meynard Keynes called him “the last of the magicians”. Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, whose system we still use in the classification of life forms, dreamed up a deeply racist classification of human beings (which included mythical species like homo sapiens monstrosus) that still influences contemporary discourse. And so on.

At the end, our villains – the Queen of the Night, Monostatos and the Ladies – are banished to Eternal Night. Sarastro claims the victory, as Pamina and Tamino are initiated into his ideas of beauty and wisdom. And we walk out of the theatre into the 21st century, at the apocalyptic endgame of all these self-serving fantasies of patriarchal authority. It’s a pretty bleak ending, when you think about it, both metaphorically and literally.

But equally, and at the same time, you can simply enjoy this exhilarating explosion of imagination and music. Delight and pleasure are, after all, complex things.

The Magic Flute, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder, directed by Suzanne Andrade & Barrie Kosky. Musical direction Jordan de Souza and Hendrik Vestmann. Staging by Suzanne Andrade and Barrie Kosky, animation by Paul Barritt (1927). Conceived by Suzanne Andrade & Paul Barritt (1927) and Barrie Kosky. Komische Oper Berlin, Barrie Kosky and 1927. Presented in association with West Australian Opera and West Australian Symphony Orchestra, Perth Festival. His Majesty’s Theatre until February 23. Bookings Adelaide Festival March1-3 Bookings

Contain theatrical smoke

Assisted hearing and wheelchair access

4 comments

The dialogue in Magic Flute is never sung, it’s spoken. The opera is a Singspiel, forerunner of today’s musicals.

Thank you! Corrected.

Forgive the pedantry, but it may be of interest that in Mozart’s time the idea of giving away your best tunes in the overture hadn’t occurred to most composers. Opera was an Italian art form and was about brilliant display; the singing, the decor, the costumes and the score. It was expected the composer, as well as providing hours of (hopefully) great music, would dash off a stand alone sinfonia to shut the audience up. This lasted well into the 19th Century with Rossini. The music in his most brilliant overtures, like William Tell and The Thieving Magpie is never heard again in those operas.

So with Mozart, except the German language pieces; The Abduction from the Seraglio and Magic Flute. The Seraglio intro directly quotes music from later and although the Flute overture doesn’t quote melody it quotes once at the beginning and then in the middle the three chords that suggest the initiate knocking at the door seeking admission into the Masonic Lodge. The Flute overture is a mix of both ideas then, as is the piece itself; a panto plus high art. These two operas were part of a political push to champion German art so the break with tradition was very deliberate. As national/imperial regimes co-opted culture they insisted opera move away from the old fashioned, somewhat decadent Italian style and use native languages and more integrated overtures. Once the Romantic movement conquered the opera house, composers used the overture to set up the sound world of the piece by using music from the body of the score. Carmen does this famously. And Wagner turned musical motifs from the score into Preludes that are whole symphonic works, especially in Tristan and Parsifal, to induce the trance we’re supposed to drift in sitting through these operas. Using your best tunes also became the norm in lighter works. Gilbert and Sullivan overtures use melodies from the show and Broadway musicals do the same.

Thank God Kosky cut all the spoken dialogue, nothing kills a night of great singing more than singers talking.

Thanks Al! As you have probably guessed, I know a bit more about the Rosicrucians and alchemy and so on than I know about the musical history of opera 🙂 I understand e flat in the overture and the opera also references Masonic symbolism?

Comments are closed.