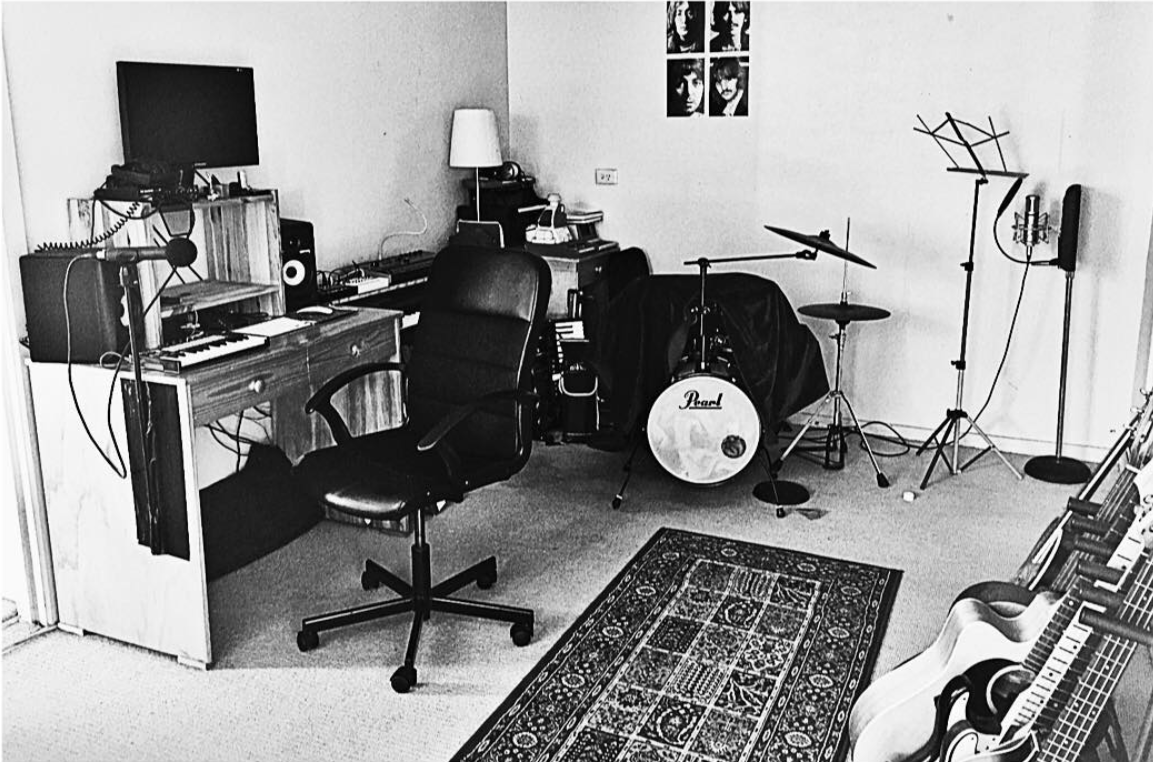

Witness sound editor Ben Keene gives us a peek inside his editing studio, and his experience with the “musical illusion”: the song of conversation

The first editing job I ever did involving the spoken word was for a meditation app. This was a challenge because meditation recordings by their nature are soporific. The practitioners I was recording and editing often spoke in a monotone, staying with the same tone for about an hour at a time. Trying to pay attention and edit out small mistakes was very difficult.

After a few sessions, I started to lose my grip on reality. Drooling in front of my computer, making edits while half listening to sweeping generalisations about how to deal with panic attacks (and once, a well-meaning but ham-fisted and improvised attempt to walk someone through thoughts of self-harm).

This kind of performed voice is not that interesting for me: its restricted nature is hard to engage with. I find editing animated conversation far more fascinating and fulfilling. This is because, even though you may not realize it, every time we talk, we are singing. It’s a beautiful fact of human communication that tone (or, if you want a musical term, pitch) is a major part of how we gather information. It suggests things like mood or intention, expresses irony or conveys whether we’re asking a question.

If you’re editing an interesting conversation, the rhythm and pitch flows and fluctuates constantly. It is my task as an editor cut out all the ums, ahs and stutters that litter a real life conversation, to make it more palatable to the external listener. While the stutters go un-noted when we hear them in real time, the act of recording distorts them. Because they no longer takes place in real time, they register as more significant.

When you listen to the podcasts on Witness, do you notice the edits? From the pit of my soul, I hope not. I want to create an illusion, a conversation that would never take place in real life. This means keeping intact the flow and song of a conversation, while still cutting as much unwanted material as possible.

Sometimes it’s best to keep an um or a stutter, because to cut it out would show my hand. But in any interview you listen to (if the job has been done properly) a lot of material has been cut out in order to create a feeling of certainty to the listener. In the moment, a speaker may have been constructing a thought in real time, with long pauses and several re-casts of sentences: but in the recording, you only hear a little of that process.

I don’t do this to create something fictitious. My ultimate desire is to make the conversation clearer to the listener. I liken it to the slight altering of photos, much as in the case of John Paul Filo and his photo of the 1971 Kate State Massacre. A student of photojournalism, he captured an iconic image of a woman screaming over the body of a gunned-down friend. It’s a powerful image that makes a statement about America’s relationship to gun laws.

However, there was a fence just behind the focus of the shot, and it looked as if the woman had a pole growing out of her head. The pole was unimportant and in fact detracted from the impact of the photo, so Filo removed it with some editing tricks. At the time, this was seen as highly unorthodox and controversial, but as photo-editing has developed it has become the norm, with both positive and negative implications.

Of course, editing includes the risk of changing the meaning and intent of an image. It’s a line you must judge on a case-by-case basis. While John Paul Filos’ intention seemed pure enough, there are countless other examples of photo alteration that do change the meaning of an image. It is my responsibility to make a point clearer, not to alter it.

When I’m editing an audio interview, a most peculiar thing happens. Almost by magic, the collection of words start to actually sing. Not metaphorically, but in reality. It’s an illusion that Diana Deuch articulated beautifully in her 1995 CD “Musical Illusions and Paradoxes”:

In our final demonstration, speech is made to be heard as song, and this is achieved without transforming the sounds in any way, or by adding any musical context, but simply by repeating a phrase several times over. The demonstration is based on a sentence at the beginning of the CD Musical Illusions and Paradoxes. When you listen to this sentence in the usual way, it appears to be spoken normally – as indeed it is. However, when you play the phrase that is embedded in it: “sometimes behave so strangely” over and over again, a curious thing happens. At some point, instead of appearing to be spoken, the words appear to be sung.

This is something a sound editor must fight against, because there’s a point where I cannot hear what is being said properly anymore. The music has taken over. I’ll be forced to leave it for a time and return to the phrase, hoping that the music has left me.

All the same, it persists. I haven’t heard the phrase “sometimes behaves so strangely” in years, but sometimes I still find myself humming its melody, its brief but oddly beautiful music. Its song.