Charles Manson as the usher of 21st century psychosis: Robert Reid reviews Sneakyville

Just as Alan Moore’s From Hell presents Jack the Ripper as the midwife of the 20th century, Christopher Bryant and Daniel Lammin’s Sneakyville gives us Charles Manson as the usher at the door of the 21st. Their dramatisation of recent-ish history – a play of two halves or more precisely, one half and two quarters – is woven through with nods to contemporary issues and real world resonances.

Because reasons, I am quite familiar with the story of the Manson Family: I’ve read Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter-Skelter cover-to-cover several times and watched a bunch of the documentaries. I don’t think I’ve researched as much as Bryant. His portrayal of the Family, their two-day war on the pigs and the trial that followed is a greatest hits of the Manson Family oeuvre. Their story is the most compelling part of the evening, and it’s a long evening. Long but, impressively, always engaging.

The first half is a masterful retelling of the circumstances around the notorious Sharon Tate/LaBianca murders by Charlie Manson’s Family, a series of killings in 1969 that claimed the lives of six people. Four members of the Family invaded the Los Angeles home of married celebrity couple, actress Sharon Tate and director Roman Polanski, murdering Tate (who was eight and a half months pregnant) and four other people. The play is rich with detail, which is good because the second half asks its audience to be familiar with much of the Manson lore.

Bryant renders the voices of Manson and the Family with a concise ear for rhythm and cadence, acutely capturing the jinky, poetic tumble of messianic pop philosophy. Manson (Wil King) is all smiles and ingratiation, clever jokes and word play. He dances around the truth, around the questions of who he is, who he isn’t, the nature of the society around him.

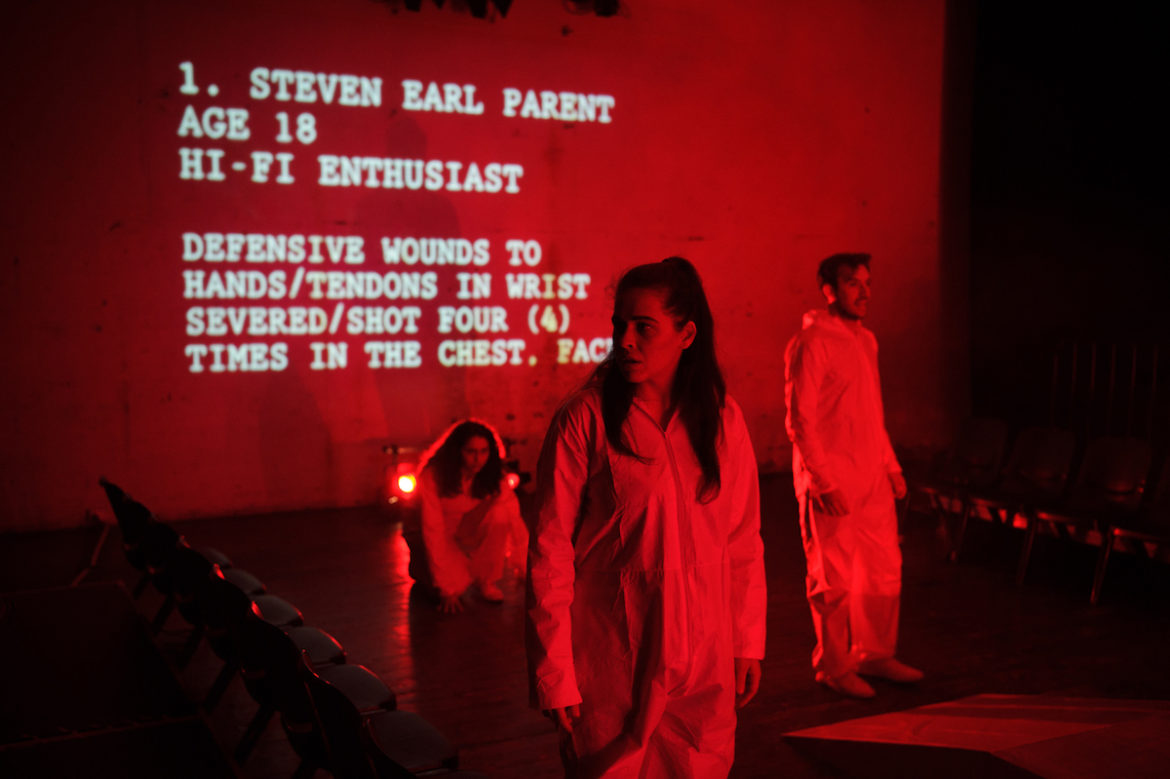

The Family – Susan Atkins, Sandra Good, Tex Watson, Patty Krenwinkel, Linda Kasabian and Barbara Hoyt – are shared between the rest of the ensemble (Kristina Benton, Julia Christensen, Patrick Durnan Silva and Grace Travaglia) and the energy crackles between them. They’re dressed in white paper suits, with a semitransparent curtain drawn between the performance and the audience for some scenes. It creates an air of clinical detachment, suggesting a forensic investigation as well as the impenetrability of historical events and the blurriness of recollection.

Towards the end of the first act, the play becomes a list of names and dates: actors step out of their roles, scripts in hand, and read out the significant events in the Manson story after the trial, up to the 1994 demolition of the house where the Tate murders happened. The cast recounts the Family cultural influences: books, documentaries, movies, telemovies, rock bands. (Did you know Trent Reznor had been the last person to live in the house and recorded The Downward Spiral there? I didn’t.) The final event, in 2018, is the beginning of a switch from documentary-style play to fiction. Manson joins a hunger strike that will eventually kill him. (He actually died of cardiac arrest as a result of colon cancer – but that’s beside the point.)

The second act begins with a journalist (Travaglia) who interviews Manson while he is on hunger strike during the last 40 days of his life, doted on by his latest and last adoring teenage girl, Star. It gives Manson back his cult leader status and his youth, his audience and the manipulated young women. It then segues to an Australian call centre worker who may be talking to an aged Family member, Sandra Good, or may be imagining these conversations as his boredom drifts towards darkness.

The length of the show starts to tell here, as the driving impetus of the Tate/LaBianca murders is missing. In any case, the energy had gone out of the Family by 2018: we watch Manson wasting away, talking the same old semi-mystical bullshit that got his victims killed. The twists and turns of his self-justifications and self-analysis are entertaining, and Bryant turns them out very convincingly, but there isn’t much drama in watching someone who has simply decided, without any opposition, that he wants to die. The best moment is between Manson and the reporter’s unborn child: he kneels down to feel the baby kick and declares that “there’s a little bit of Manson in him.” Death whispering itself into the promise of renewal.

Meanwhile Sandra Good (Benton) has been keeping the Family’s ATWA (air trees water animals) philosophy alive on a web 1.0 site, complete with egregious font choices and garish colours. She calls a mobile company to abuse them generally for being a corporation but instead ends up talking to the call centre worker (Silva) who offers to her help redesign the website. They become close, in their way, exploringover the phone their respectively waning and nascent sociopathies, chasing after the spirit of Charlie that lives on in both of them.

It’s a shouty play. Very entertaining, but very shouty. The momentum that the Manson Family story imparts to the more contemplative second act almost carries it all the way through to the end.

I don’t have the same sympathy for Manson that this production has. It concludes with what seems like an appeal to his humanity, claiming that while we, the media and its junkies, focus on the sensational aspects – the cult, the drugs, the sex, the murders – he was also a sensitive musician, a poet and visionary.

The Family says Charlie is love, not hate: he represents more than his humanity. The mythic Charlie is more than the real Charlie. But it’s not enough to turn the glare of Charlie Manson back on us and say, hey, he was an artist too. That’s another way of falling under his spell. He makes you think he’s special. He’s not. These days, manipulative psychopaths are common as dirt.

It’s not remarkable that artists are sometimes murderers. Humans are sometimes murders. A lot more than sometimes, in fact, and in many more gruesome and prolific ways than Manson and the Family. The most notable thing about the Family was their banality. During the trial Manson himself said: “These children that come at you with knives, they are your children. You taught them. I didn’t teach them. I just tried to help them stand up.” The most terrifying aspect of this story remains the fact that the Family were the children of middle class America.

Sneakyville by Christopher Bryant, directed by Daniel Lammin. Production design by Nathan Burmeister, lighting by Alexander Berlage, sound design and composition Kellie-Anne Kimber, AV Design by Justin Gardam. Performed by Wil King, Kristina Benton, Julia Christensen, Patrick Durnan Silva and Grace Travaglia. A Before Shot production at fortyfivedownstairs. Until August 12. Bookings

fortyfiveownstairs provides no access information.