Robert Reid attends the first act of an extraordinary immersive performance of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya in a country farm house.

It’s a perfect day for Chekhov in rural Victoria. Grey and forbidding, with sudden drenching rain as we drive through the Macedon Ranges towards the house in Eganstown where La Mama is presenting a two-day-long immersive production of Uncle Vanya, conceived and directed by Bagryana Popov.

Easy to miss from the highway, the property is signposted with a small handwritten cardboard sign and a solitary red balloon tied to the gate. The most desultory 21st birthday welcome ever. The drive up to the car park is surrounded by tall trees ominously shedding their bark. There are ghosts everywhere here.

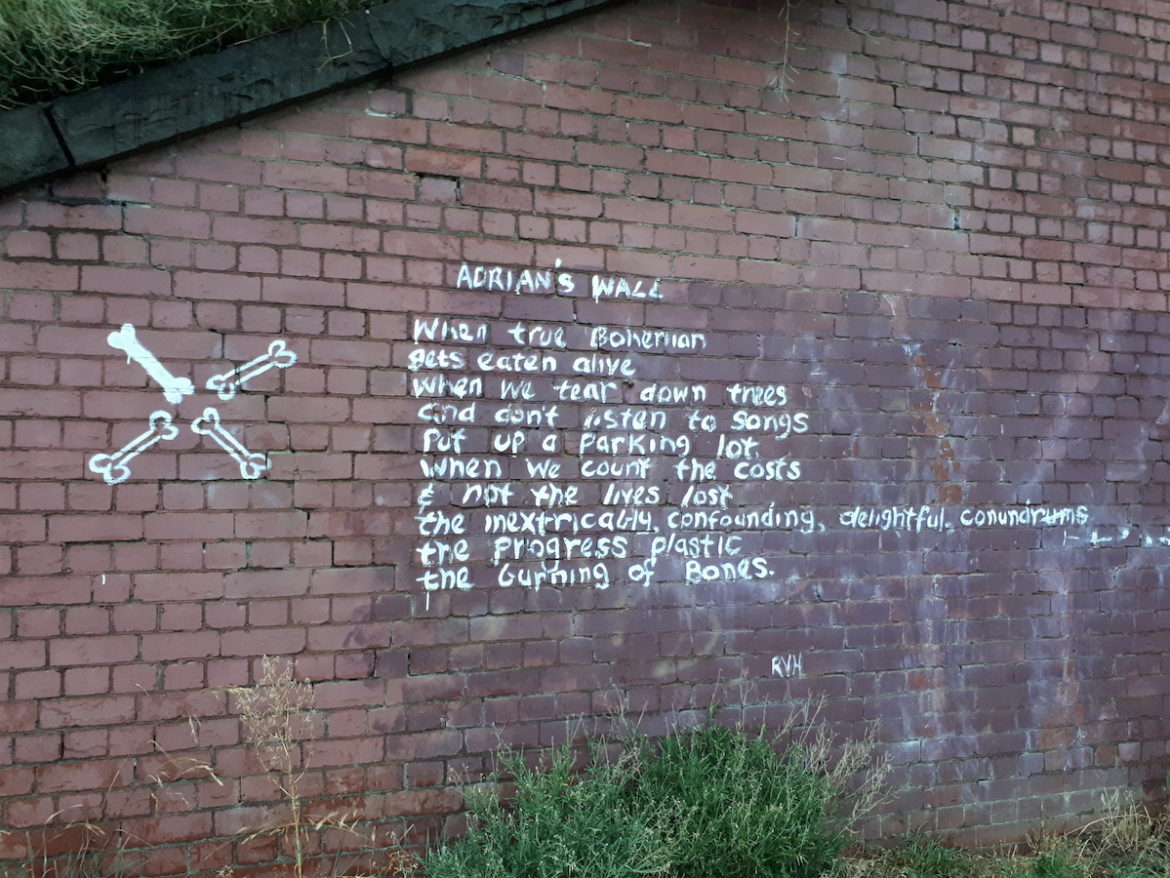

On a bridge out of Daylesford, heading to the property on the Midland Highway, we notice graffiti on the rail bridge. It’s a poem of dubious attribution, which reads:

Adrianʻs wall

When true bohemian

Gets eaten alive

When we tear down trees

And don’t listen to songs

Put up a parking lot

When we count the costs

And not the lives lost

The inextricably confounding delightful conundrums

The progress plastic

The burning of bones

RVH

*

Popov and her cast have been working on Anton Chekhov’s classic, Uncle Vanya, for half a decade or more. It has been performed in historic houses around the country including Avoca and Stieglitz, and goes on to Bundanon house in NSW. Popovʻs production, presented this weekend at Corinella House in Eganstown, includes all four acts over two days. It adheres roughly to Chekhov’s timeline – Act One is at 3pm, Act Two in the evening, Act Three the following day and…you get the drift. Interspersed between the acts are talks on related subjects, free time to explore and interact with performers, informal campfire story-telling and a guided walk around the property.

Full disclosure: because of reasons, we didn’t stay the whole weekend, only Act One. Which, on reflection, works well for me. I already have a lot I want to say about what I did see.

There is a strong focus on the environmentalist passages in the play. The media material about Popovʻs Vanya goes so far as to call it the world’s first environmental play. The talks which follow the first act focus on climate and environment as well.

Certainly, there are references throughout the text to the dying landscape and the duty we owe to future generations to protect it. In turn-of-the-century Russia, these notes resonate more with the oncoming collapse of the old world empires only a few decades in the future. The forests and trees in Chekhov’s text are symbolic of the decaying Russian middle class, the rot at the core of the Serebryakov family and their friends.

It strikes as immediately ten minutes out of Daylesford as it did at the Moscow Art Theatre: in both contexts we witness the decaying middle class arguing around the kitchen table about trees and grass, the destruction we’ve wrought on the world, the legacy we will all leave. These strike me as very middle-aged concerns, too.

This Vanya is set on location on a rural Victorian Goldfields farming property. The text is localised where appropriate and the actors work with a loose relationship to the translation while honouring the individual beats and moments of the story. It’s instantly recognisable as Uncle Vanya, but with a relaxed open-flannelette-shirt vibe about it. Which makes it, in fact, very comfortably watchable.

The production takes place throughout and around the property. Act One begins in the kitchen. It is per force a small audience, not more than thirty at a guess, which is not unusual for La Mama. We crowd around the table at which Marina (Liz Jones) and Dr Astrov (Todd MacDonald) sit waiting. Having paid her and the company’s respects to the traditional owners of the land, the Dja Dja Warrung and their elders, Popov addresses us briefly with some procedural details and signals the actors to begin.

The line between not having begun and beginning is already remarkably blurry. We’re all in the kitchen together, illuminated by the grey afternoon light coming in through the large windows. McDonald interacts with the audience near him as they stumble in to find seats, offering seats that are free, which are comfortable, which we can sit in. Is it MacDonald being a considerate actor, making sure audience don’t sit in seats that will be needed by actors later in the act, or is Dr Astrov being a confident friend of the family, good naturedly demonstrating his belonging here by offering where the new-comers to the house may sit? He betrays this same need to be seen to belong by demanding Marina recount the story of how she knows him.

This uncertain border between literal reality and and the fictions of the play strikes me most about Popovʻs production. Once we are into the play proper, it’s obvious who is in character and who is part of the audience. Yet one audience member sits at the table between Vanya (James Wardlaw) and Marina. Telegin (Richard Bligh) has to retrieve his guitar from behind me. Dr Astrov has to get his bag from behind us. We move out of their way, they apologise for the inconvenience. But who are we? We’re not guests or friends of the Serebryakov family. Nor are we an invisible audience, breathless behind the fourth wall.

We’re more like ghosts, haunting the estate.

*

The actors use the whole of the property, entering from outside and going about their business in the rest of the house, while we remain in the kitchen where the action is. Outside, through the windows, I can see Sonya (Natascha Flowers) working in the garden once she leaves the scene in the kitchen. A car drives along the drive way not long after Dr Astrov has left and it’s easy to imagine he is in the car. It’s not inconceivable: how far does the magic circle around this world extend?

Vanya and Yelena (Olena Fedorova) stalk off through the house arguing at the end of the act and their voices fade into the lounge. Popov comments occasionally through the proceedings, perhaps giving suggestions or coded directions, to the actors as their characters. It reminds me of Tadeusz Kantor’s interventions, shaping the moment to suit the demands of the scene, shaping the scene to suit the demands of the moment.

Fedorova is the only one who speaks with a European accent – her own, of course. Through her the production reaches out to Jeanne in Betty Rolandʻs 1928 play The Touch of Silk. A different family, a different situation and a different narrative; but I think the resonance echoes the note of transplanted European standards of beauty and culture, struggling to survive and maintain colonialist narratives that are present in both Rolandʻs play and Popovʻs Vanya.

The silent subalterns that haunt Popovʻs production are the Dja Dja Warrung, the traditional owners of the land on which this European classic is presented, whose river was ground into silt by mining companies dredging for gold. Those companies were owned and run by the men that the local cities are named after. The middle-class rot here is a very different one to the ennui of the 1890ʻs Russia, but it’s very ʻhere’, nevertheless.

At the end of the act, Popov tells us that we have fifteen minutes or so of free time in which we are free to explore the open areas of the house and property and to talk to the actors. Popov explains that they may answer us or they may not. Here the real blurs strongly again. Are the actors themselves once more, free to mingle as they would after any other La Mama show, or are they still in character?

The property is, in effect, playing itself and signals similarly across both fictional and real landscapes. Out in the garden, Sonia/Flowers continues to work with the rake. She’s being filmed by the documentarian recoding the production. Vanya/Wardlaw approaches her and they talk about chores around the farm. He’s Vanya now, I decide, and she’s Sonia. But for my benefit, or the camera’s, or neither? Exploring elsewhere, Professor Serebryakov (John Bolton) is in bed under a crocheted rug in his room, having retired at the end of Act One. He’s talking to three or four audience members who surround him, sitting and standing like concerned relatives around a hospital bed. I can’t hear what they’re saying.

In the lounge someone plays the piano (I can’t see who) and Maria (Meredith Rogers) talks to those gathered, but then I think she mentions the Malthouse and so for a moment it’s simply Rogers speaking. Then again, who’s to say Maria hasn’t been to the Malthouse? She’s a widow to a privy councillor and must know her art and culture. Certainly, there must a few subscribers living out Daylesford way. My wife goes to pick fresh tomatoes from the garden with Vanya and brings them back into the kitchen to share with the audience and cast as we gather for two short talks on the local ecology and its preservation.

Throughout both talks, I’m conscious again of the silent presence of the traditional owners of the land, the Dja Dja Warrung. The talks focus on climate change and cover traditional farming practices that kept the land fertile for thousands of years, now lost to European land conservation methods, and the damning and dredging of the river by gold mining companies. Archaeologist Dr Susan Lawrence tells us how the original miners devised ways to speed the process of mining for gold by taking the water from the river to the diggings. At this point one of the audience couldn’t contain herself and asked, “Yes, and who’d they pay for the water?” I think this is a pertinent question that should be asked of all of Australia’s many Doctor Astrovs and Uncle Vanyas.

We know, if we know the play (and who would come to a two-day long production that didn’t already know the play?) that Dr Astrov will refuse Sonia. We know that Vanya will pursue Yelena and will make his attempt to shoot the professor. And fail. Over the two days of this weekend we know that their middle-class secrets, already buried too close to the surface in this family, will be revealed. The burning bones of ʻRVH’s’ landscape stolen lately by parking lots from the true bohemians, stolen first of all from the Dja Dja Warrung by industrialising European modernism, scrape at the heavy grey Macedon ranges sky like the dead tree on the horizon we can see from the kitchen window.

The question left open at the end of Act One, and by the production itself, is how complicit will we become? How complicit already are we, white ghosts who stand aside among the ghosts in the landscape, merely watching? While it’s a sobering reminder of the ubiquity of climate change, highlighting the environmentalism of the play strikes me as something of a misdirection. Instead of confronting the social issues that are directly impacting us, we consider with detachment the approaching catastrophe those issues have manifested in the world around us. We bemoan the effect and do not address the cause.

I’m not sure that we would have been up for the whole weekend anyway, even if circumstances had not intervened. It’s a long time to stay in a work, a long time to stay attentive to the affordances of landscape and narrative. Returning to a hotel or B&B for the night, after dinner at the pub and an hour or two of WIN TV before Act Two, might be jarring. Or it might be an endlessly deepening referential experience.

I’d love to hear from people who saw the entire work – I know there were at least a few Witnesses among the guests of La Mama and the Serebryakov family. I’d be fascinated to hear how the complexities of the performance developed over the weekend.

Uncle Vanya (Act 1) by Anton Chekhov, Adapted and directed by Bagryana Popov, La Mama, presented at Corinella House, April 14. Performed by James Wardlaw, Natascha Flowers, Todd MacDonald, Liz Jones, Olena Fedorova, John Bolton, Richard Bligh and Meredith Rogers. Dramaturgy by Maryanne Lynch. Sound design by Elissa Goodrich.