‘It’s a different beast altogether than Who’s Afraid of the Working Class, and not only because all the writers are older’: Alison Croggon on Anthem

Anthem is one of the most heralded of this year’s Melbourne Festival offerings. The idea is that it revisits the Melbourne Workers Theatre’s most famous product, Who’s Afraid of the Working Class?, bringing together the same four writers – Andrew Bovell, Patricia Cornelius, Melissa Reeves and Christos Tsiolkas – to once again review the state of the nation through the eyes of its underclass.

Who’s Afraid of the Working Class? has attained a kind of legendary status in the two decades since it was first produced, buoyed not a little by the late-rising star of Cornelius, whose year has included winning the mysterious $250,000 Windham–Campbell prize and debuting at the Venice Festival. But back in the day, despite my admiration of some of the writers, this collaboration – directed then by Julian Meyrick – didn’t float my boat. I fled at interval, after being driven to distraction by the twee faux-povo diction of Bovell’s abject youth.

I had little desire to see the latter day version, and moreover, since I had only seen half of the original, I felt that I was probably the wrong person to write about it anyway. But my esteemed colleague, Dr Robert Reid Esq, broke his elbow over the weekend and was suddenly out of commission. So there I was.

After all, it was 20 years since last these writers got together, and that’s a lot of words under the bridge. And this time they’re directed by one of the best in the business, Susie Dee, who is also a formidably good dramaturg. I put on my optimistic glasses and headed to the Playhouse Theatre for the final performance in its short season.

The opening scene – the first in Christos Tsiolkas’ play Brothers and Sisters, about a successful corporate brother returning from France to distribute largesse to his marginalised siblings – made my heart sink. A scene on the Eurostar conducted above the stage between the corporate brother (Thuso Lekwape) and a random middle class British woman (Erin Jean Norvill), it featured the kind of sledgehammer talking-head politics that makes theatre brain-deadening. Brexit, racism, idpol and middle class hypocrisy all got a guernsey.

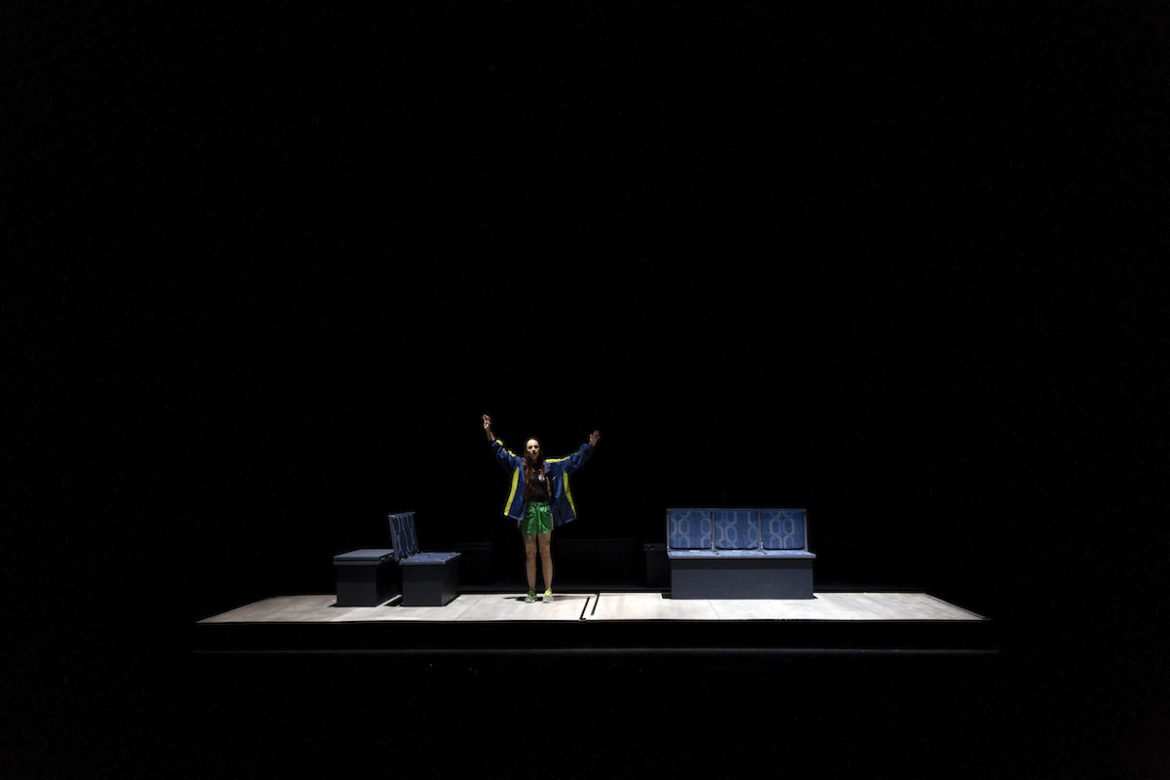

But after that, things looked up considerably. The cast flooded onto Marg Horwell’s spectacular set, passengers on suburban trains enacting a poetic chorus of collective thoughts (Andrew Bovell’s Uncensored). Using the train network is a brilliant conceit, bringing together all kinds and classes of people temporarily together into the same public space.

The four plays are deftly woven together with Irene Vela’s score for strings, Resistance, which is played live on stage by Jenny M. Thomas (violin) and Dan Witton (double bass). Ruthy Kaisila weaves her way through the passengers shaking a tin (“pay up, you cunts!”) as a kind of muse, singing breathtaking versions of three standards – Waltzing Matilda, I Still Call Australia Home, Amazing Grace – that ring ironically through the auditorium.

One of the real pleasures of this production is its choreography and stage craft, which is always various, at once alive and livening. At one exhilarating point it turns into real dance, but it’s always physically vital, focusing our attention on the performers. It’s brilliant to see what Dee can do when she has, for once, the resources of a main stage to articulate her directorial vision. It makes stunning theatre: at once bold, arresting and clear. Another pleasure is the consistently fine and various cast; for once the stage did look like the streets of Melbourne, with people of all ages and races.

The stand-out stories are by the women: Cornelius’ Terror, a delicate and painful encounter between a former maid (Amanda Ma) and her mistress (Maude Davey) now fallen on hard times, and Reeves’ 7-Eleven and Chemist Warehouse, a love story, a comical romance between two pissed-off, ripped off young employees (Norvill and Sahil Saluja) who go on a rampage against capitalism and hold up the wrong corporation.

Bovell’s Uncensored evolves into an encounter between a single mother (Eva Seymour), a nice middle-aged woman (Norvill) and a ticket inspector (Osamah Sami) which unpacks, perhaps a little too patly, the middle class judgments that arise around a young, stressed, failing parent. Seymour’s character is virulently racist to the ticket inspector (bad!) but she’s having a truly terrible day (at last we understand!) I did wonder about the go-to idea that the underclass person is the one who must display racism; and I wondered a little more about the necessity for its display at all, which in my opinion is a difficult ask for a white writer. At what point is it merely enacting trauma to make people like me feel good about ourselves?

The weakest play is Tsolkias’; it’s very clear that he’s not, like his colleagues, an accomplished playwright, able to create characters and actions that reveal politics, rather than representations that symbolise different ideologies. His siblings have fathers from four races – Arab, Anglo, African and Aboriginal – and despite some excellent performances, notably from Carly Sheppard, they are never really imagined into being real people. Notably, this is the only story that falls into sentimentality.

I did have a few questions afterwards – whether perhaps it might have been more interesting to bring together four new writers to illuminate the intersectional themes that run through it; what it means that I was watching it in the plush environs of the Arts Centre Melbourne rather than in the poor theatre space of the Trades Hall. It’s a different beast altogether than Who’s Afraid of the Working Class, and not only because all the writers are older.

Woven together as a whole, however, the sum is bigger than its parts. Anthem is, for the most part, gripping and accomplished theatre saying difficult things about where we are now, and that’s much rarer than it should be.

Anthem, written by Andrew Bovell, Patricia Cornelius, Melissa Reeves and Christos Tsiolkas, composed by Irine Vela, directed by Susie Dee. Design by Marg Horwell, lighting design by Paul Jackson, music direction and sound design by Irine Vela. Performed by Maude Davey, Reef Ireland, Ruthy Kaisila, Thuso Lekwape, Amanda Ma, Maria Mercedes, Tony Nikolakopoulos, Eryn Jean Norvill, Sahil Saluja, Osamah Sami, Eva Seymour and Carly Sheppard. Musicians Jenny M. Thomas and Dan Witton. Playhouse, Arts Centre Melbourne, for Melbourne Festival. Closed.